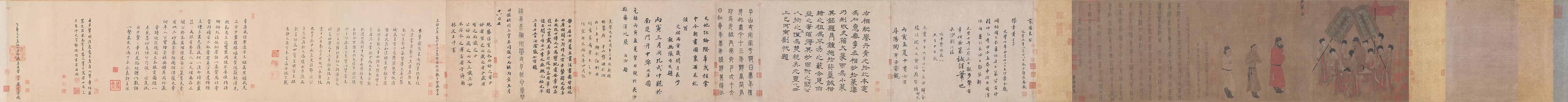

This historical painting captures a pivotal diplomatic event in early Tang Dynasty China. During the 7th century, as the Tibetan Empire (present-day Tibet) rose to prominence under its 32nd ruler Songtsen Gampo – a visionary leader renowned for military prowess and political acumen – the Tibetan king dispatched envoys to Chang’an (modern Xi’an) in 634 CE seeking marriage alliance with the Tang court. Emperor Taizong approved this request, betrothing Princess Wencheng of the imperial clan to the Tibetan ruler.

In spring 641 CE, Tibetan chancellor Gar Tongtsen arrived in the Tang capital to escort the princess, while Emperor Taizong appointed Li Daozong, Minister of Rites and imperial clansman, to accompany the bridal procession. Beyond cultural texts, the princess’ entourage included master craftsmen from diverse fields, significantly advancing Tibet’s economic and cultural development. This union ushered in prolonged peace between the two empires.

Artist Yan Liben immortalized this Han-Tibetan diplomatic milestone through his brush. The composition portrays Emperor Taizong receiving Tibetan envoy Gar Tongtsen in the palace interior. The emperor sits imposingly on a six-maiden-borne litter (Bunian, namesake of the painting), flanked by three attendants holding ceremonial fans and canopies. Three figures stand before the throne: a crimson-robed protocol officer at right; the distinctively attired Gar Tongtsen bowing respectfully at center; and a white-robed palace official at left.

As court official Yan Liben likely witnessed this historic audience firsthand, his figures pulse with authenticity. Each character manifests distinct traits – the emperor’s imperial dignity, the envoy’s capable humility, officials’ deferential poise, and maidens’ youthful vitality – all rendered with nuanced cultural contrasts between Tibetan and Han subjects.

Executed in meticulous gongbi style, the work features masterful ink lines that vary rhythmically to define forms, complemented by rich mineral pigments. The portrait-like treatment of central figures, particularly in conveying Emperor Taizong’s commanding presence and Gar Tongtsen’s composed demeanor, demonstrates Yan’s unparalleled skill in combining documentary accuracy with artistic sublimity.

The solemn-faced Emperor Taizong sits cross-legged on his “ambulatory throne,” wearing the signature black gauze headwrap of Tang rulers. This peculiar conveyance merits closer examination. Traditionally, a “nian” carriage required wheeled transport pulled by draft animals, but here the emperor’s “bunian” (literally “stepped carriage”) defies convention. Instead of wheels, this ornate platform gets carried by palace maidens – two at front and rear – transforming imperial mobility into human-powered pageantry.

Observe the deliberate disproportion in scale between emperor and attendants, a common symbolic device in classical painting emphasizing imperial grandeur. The litter-bearing maidens wear distinctive pan ropes (harness straps) around their necks, their collective effort framed by two flanking attendants on each side. Three additional maidens complete the procession: two waving ceremonial fans, one upholding the vermilion ceremonial canopy – that iconic umbrella-like emblem of imperial authority.

The maidens’ costumes reveal Tang fashion intricacies. Their translucent sheer silk gauze robes subtly contour feminine silhouettes, sleeves narrowing into elegant cuffs. High-waisted long skirts ascend to ribcage level, secured beneath short jackets tucked neatly at the waist. The clever sash arrangement creates visual intrigue – while functional waist ties allow practical skirt adjustment (hiked for mobility during duties, lowered for ceremonial grace), the draped fabric above the belt forms decorative pouch-like folds.

In this frozen moment, practicality prevails as the working maidens hike their skirts to reveal soft red satin slippers and striped trousers beneath – an authentic snapshot of Tang court life where ceremonial splendor met daily pragmatism. Each sartorial detail, from the weightless drapery to the strategic layering, manifests the Tang aesthetic balancing ethereal beauty with grounded functionality.

If you are interested in Qiu Ying’s works, I also recommend watching this very famous “Han Palace Spring Dawn“.