A Defining Moment in Art History

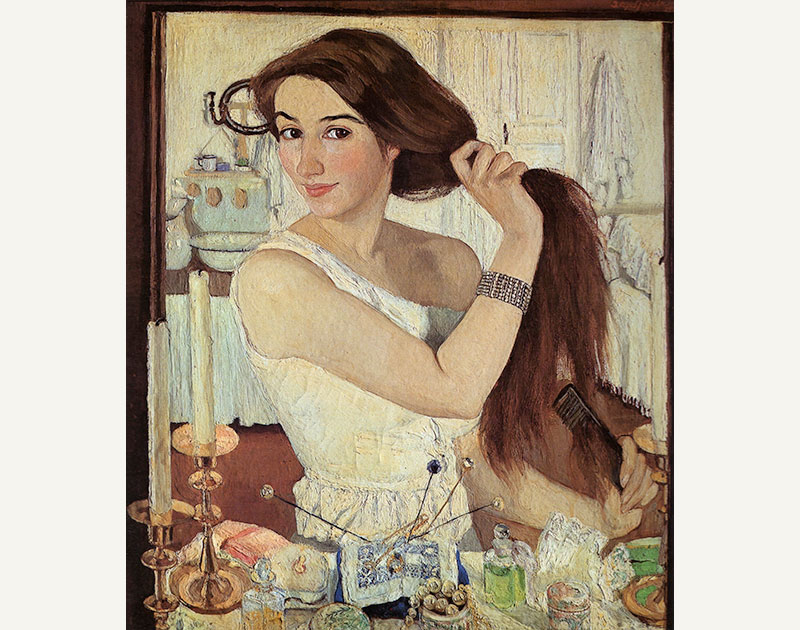

Zinaida Serebriakova’s Self-Portrait at the Dressing Table (1909) stands as a cornerstone of early modernist portraiture, merging intimate femininity with groundbreaking technical mastery. Created when the artist was merely 25, this 75x65cm oil painting—now housed in Moscow’s Tretyakov Gallery—captures a fleeting morning ritual transformed into an eternal symbol of youth and self-awareness.

Behind the Brushstrokes: Creation & Context

Amidst a snowbound winter at her family estate near Kharkiv (modern-day Ukraine), Serebriakova turned isolation into artistic revelation. Facing a large mirror each dawn, she documented herself in a white camisole with a slipped shoulder strap—a calculated “accidental” detail that echoes Renaissance Venus depictions while defying Victorian prudishness. The dressing table, laden with perfume bottles and jewelry boxes, becomes both stage and metaphor: a shrine to private womanhood rarely depicted in pre-revolutionary Russian art.

Key historical influences:

- Art Nouveau Fluidity: Soft curves in the mirror frame and fabric folds

- Symbolist Introspection: Candlelight’s warm glow contrasting with cool morning tones

- Dutch Still Life Tradition: Precise rendering of glassware and textiles

Why This Self-Portrait Changed Everything

When unveiled at St. Petersburg’s 1910 Modern Women’s Portraiture Exhibition, critics hailed it as “a manifesto of the New Femininity”. Three revolutionary aspects cemented its legacy:

- Technical Alchemy

Thin, translucent layers (glazing) create luminous skin tones—a technique borrowed from Flemish masters but applied to contemporary subjects. The mirror’s dual perspective (front/back view of the artist) demonstrates her academic training under Osip Braz while subverting traditional self-portrait formats. - Psychological Depth

The direct gaze—both self-assured and vulnerably introspective—predates Freudian psychoanalysis in visual art. Art historian Alexandre Benois (her uncle) noted: “She stares not at her reflection, but at eternity through it”. - Cultural Impact

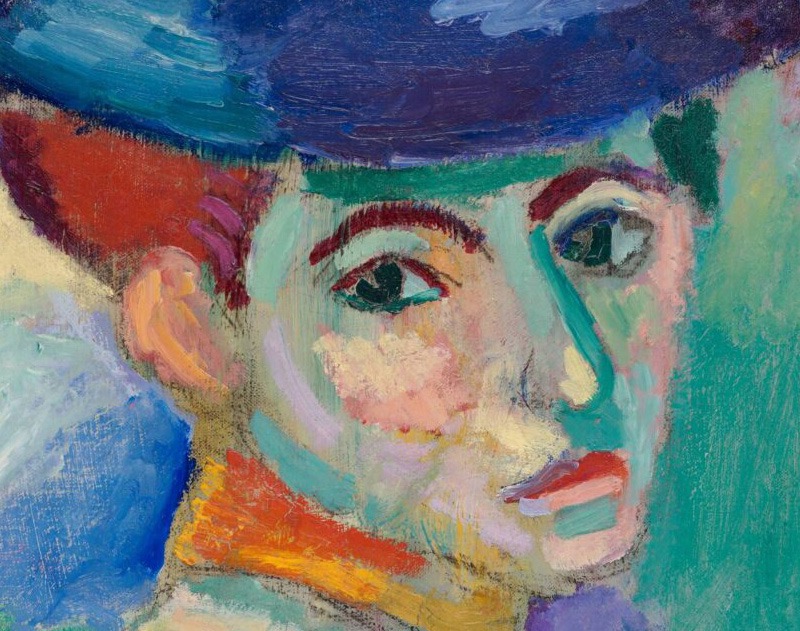

As one of the first Russian paintings to celebrate middle-class domesticity, it inspired generations of female artists like Natalia Goncharova. Its 1911 Paris exhibition version (now lost) reportedly influenced Matisse’s later interior studies.