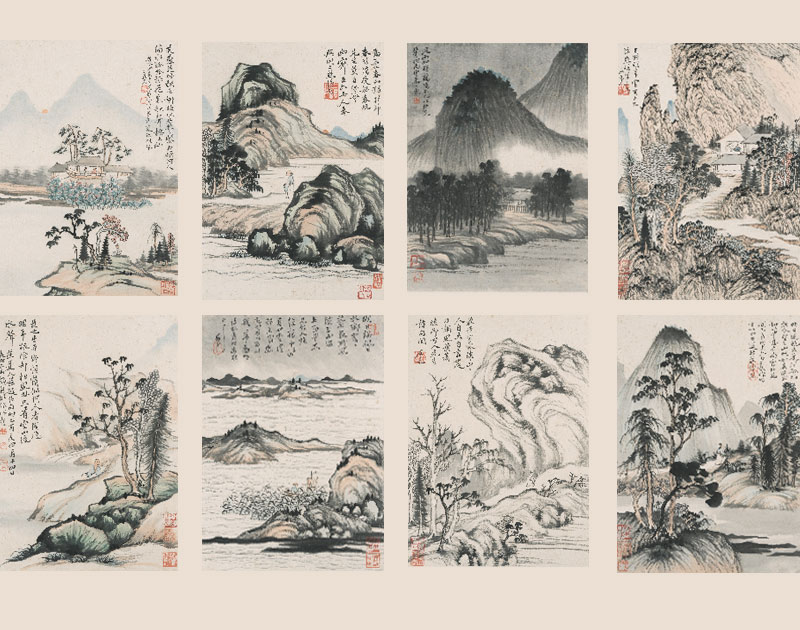

“The Xia’ao Yanxia (Roaming Proudly Through Mist and Rosy Clouds) Landscape and Figure Album” is a masterpiece by Li Jian (1747-1799), a renowned Lingnan painter of the Qing Dynasty. Created in 1789 (the 54th year of the Qianlong reign) as an eight-leaf album, it integrates landscapes and figures to express his profound contemplation of nature, reclusive living, and artistic philosophy.

This work reflects the primary influences shaping Li Jian’s painting techniques—Dong Yuan (董源, 10th c.), Mi Fu (米芾, 1051–1107), Wang Meng (王蒙, 1308–1385), and Huang Gongwang (黄公望, 1269–1354). While only the first leaf explicitly references Shitao (石涛, 1642–1707), the entire eight-leaf album profoundly demonstrates Shitao’s stylistic impact. Key characteristics such as wet brushwork with heavy ink, light crimson color washes, and slightly archaic simplicity in rendering trees, rocks, and figures all derive from Shitao’s signature innovations. Li Jian himself claimed that his painting studies only began bearing fruit after his forties; this album represents a masterpiece among his mature works. Currently housed in the Art Museum of The Chinese University of Hong Kong, it is executed in ink and color on paper.

1. Autumn Lotus by the Lake

Scene: A hermit listens to distant poetry across lotus-filled waters, mist blurring autumn mountains.

Inscription:

“When lotus blooms tint autumn,

Purple mists mirror the lake.

Who hears verses through the mist?

A celestial chant from the tower amid flowers.”

Meaning: This homage to Shi Tao’s Lotus Bay reimagines literati ideals through layered ink washes, where solitude and engagement coexist like lotus roots hidden beneath murky waters.

Cultural Note:

- Wet Ink Technique: The mist’s translucent layers mirror Shi Tao’s revolutionary “ink pooling” method, symbolizing the gradual accumulation of wisdom.

2. Solitary Spring Journey

Scene: A scholar walks alone with a bamboo staff, companions faintly visible through pine forests.

Inscription:

“For love of spring mountains I wander alone,

My robe soaked in warm breeze.

Though solitary, my joy is shared

By six or seven kindred souls.”

Meaning: The deliberate contrast between the foreground figure and distant companions visualizes Confucian collectivism tempered by Daoist individualism, echoing the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove.

Cultural Note:

- Bamboo Staff: A symbol of scholarly resilience, akin to the “iron brush” metaphor in Chinese calligraphy.

3. Rooster’s Cry in the Storm

Scene: A thatched hut emerges through stormy mists, rooster crowing within as rain pelts ink-darkened peaks.

Inscription:

“Though wind and rain darken the sky,

The rooster never ceases its cry.”

(Adapted from The Book of Songs, 300 BCE)

Meaning: Subverting Dong Yuan’s serene landscapes, Li transforms a Confucian allegory of perseverance into a visual symphony of ink washes, where hope glimmers in the hut’s lone window.

Cultural Note:

- Rooster Symbolism: In Chinese tradition, roosters represent vigilance and moral integrity, often linked to scholar-officials’ duty to remonstrate rulers.

4. Homage to Wang Meng & Huang Gongwang

Scene: A woodcarrier climbs winding paths through peaks merging Wang Meng’s dense textures and Huang Gongwang’s open vistas.

Inscription:

“Wang Shuming’s brush capturing Huang Zijiu’s spirit.”

Meaning: This experimental fusion of Yuan dynasty masters’ styles becomes a metaphor for artistic lineage—where every innovation grows from ancestral roots.

Cultural Note:

- “Ox-Hair” Brushstrokes: Wang Meng’s signature niú máo cūn (牛毛皴) technique mimics cattle hair texture, representing meticulous scholarship.

5. Zen of Pine and Stream

Scene: A meditating figure under ancient pines, ink swirls mimicking wind-whispers and stream murmurs.

Inscription:

“Beyond the pines’ murmuring and the stream’s song,

All worldly noise fades.”

Meaning: The minimalist palette and “soundscape” composition translate Chan Buddhist teachings into visual form, where emptiness (留白) becomes the ultimate revelation.

Cultural Note:

- Chan Aesthetics: Li’s use of negative space reflects the Buddhist concept of śūnyatā (emptiness), where meaning emerges from absence.

6. Farewell by the River

Scene: A lone sail fades into mist, willow branches droop along desolate reedy banks.

Inscription:

“Tomorrow my sail descends to watery lands,

Silent parting weighs heavy as dusk veils the peaks.

Where my old friend once stood, only green willows weep.”

Meaning: Withered reeds (dry brushwork) clash with lush willows (wet ink), juxtaposing present sorrow with past camaraderie. The scene elevates personal grief to cosmic contemplation.

Cultural Note:

- Willow Symbolism: The homophonic link between liǔ (柳, willow) and liú (留, to linger) makes willows a traditional emblem of farewell in Chinese poetry.