“Examples of Chinese Ornament”: A Victorian Reimagining of Eastern Aesthetics

Published circa 1867, this seminal pattern book by Owen Jones—pioneering British architect and design reformer—represents a curated visual dialogue between East and West. Drawing from Chinese antiquities in the South Kensington Museum (now Victoria and Albert Museum) and private collections, Jones sought to decode and reinterpret Qing decorative arts through a Victorian lens.

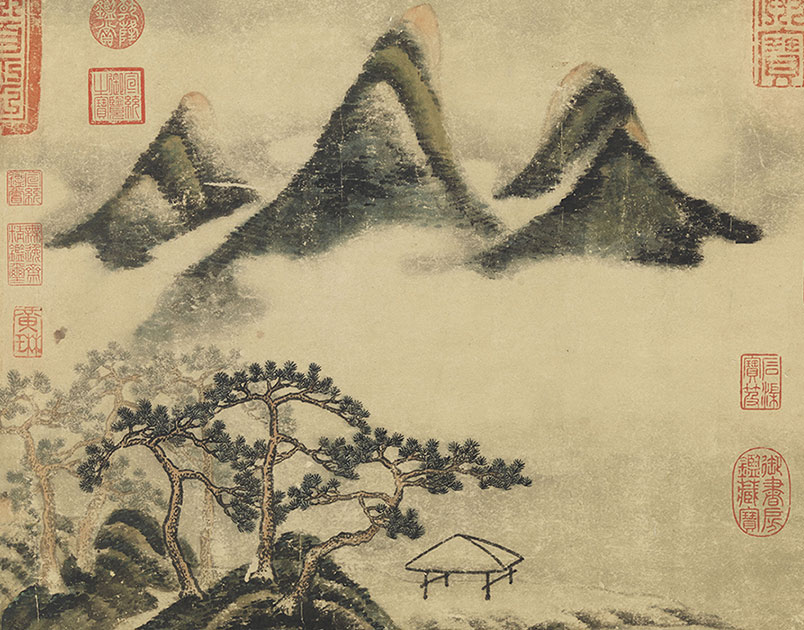

In his preface, Jones contextualized the artifacts’ arrival: “China’s recent Opium Wars and Taiping Rebellion have devastated imperial workshops, scattering these opulent decorative masterpieces to Europe. Their technical refinement and chromatic sophistication surpass anything previously seen in the West.” Yet the Victorian tastemaker offered veiled criticism of late Qing aesthetics. The selected patterns—predominantly famille rose porcelains and cloisonné enamels—embodied what Jones deemed “excessive opulence”: rigid patterns lacking spontaneity, garish color schemes devoid of subtlety.

To “purify” these designs, Jones implemented creative interventions:

- Reviving Tang-Song dynamism through scrolling lotus motifs

- Muting original color intensities by 30-50%

- Introducing breathing space within dense compositions

- Systematizing organic forms into geometric repeat patterns

The resulting plates became transcultural masterpieces—Qing craftsmanship filtered through Victorian design principles. Jones’ chromatic recalibrations transformed “vermilion-and-emerald vulgarity” (as per contemporary critics) into harmonious jewel tones that inspired the Aesthetic Movement.

Owen Jones (1809-1874): Design Alchemist

As co-architect of the 1851 Great Exhibition’s Crystal Palace and founding instructor at the Government School of Design (later Royal College of Art), Jones championed “principles of universal ornament.” His 1856 masterpiece The Grammar of Ornament established cross-cultural design analysis. The Chinese Ornament folio, created during his tenure as art director of the relocated Crystal Palace at Sydenham (1852-1854), reflects his belief in evolutionary design progress through cultural synthesis—a vision tragically cut short by his sudden death while preparing an Egyptian ornament volume.