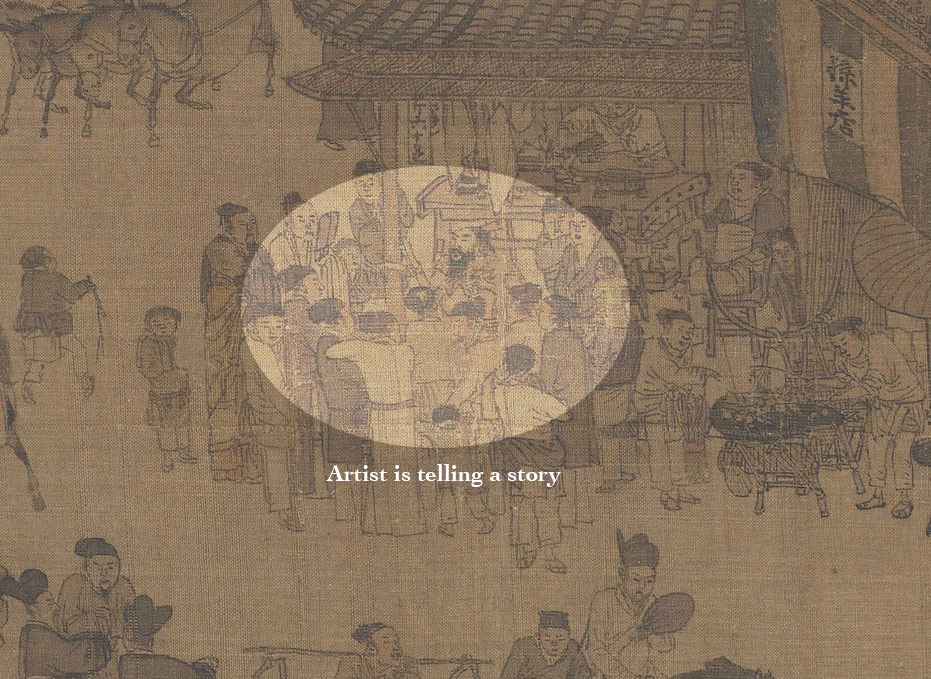

“Along the River During the Qingming Festival” is known as one of the ten famous paintings of China. Why is it famous? Chinese paintings pay the most attention to artistic conception. Painters love to paint landscapes, flowers and birds, and still lifes. At the very least, they must paint the faces of intellectuals. There are very few realistic customs paintings reflecting the life of the market. Scarcity makes things valuable. This boundary painting reflecting the urban life of the Northern Song Dynasty naturally became more unique and became the ancestor of this type. The most important thing is that this realistic long scroll shows a superb sense of drama under the author’s exquisite layout.

The artwork was painted by Northern Song artist Zhang Zeduan. It depicts the bustling and vibrant scenes during the Qingming season in and around the East Jiaozi Gate of Bianjing (the Northern Song capital, now Kaifeng in Henan) and along both banks of the Bian River. The festival of Qingming Shanghe was a popular folk custom of the time—much like today’s festive gatherings where people participated in trade and commercial activities. The painting is 528.7 centimeters long and 24.8 centimeters wide. There are about 800 people, more than 60 livestock, 28 boats, more than 30 houses and buildings, 20 cars, 8 sedan chairs, and more than 70 trees in the painting. If you zoom in on any part and take a closer look, you will find that the characters are of different classes, different clothes, and very different expressions. There are a lot of details hidden in the painting, and various activities are interspersed, which is very interesting.

The entire scroll is roughly divided into three sections: the spring scenery of the outskirts of Bianjing, the scenes along the Bian River, and the urban marketplace.

When ancient people looked at paintings, they could not spread out the long scroll to take in everything at a glance. Instead, they had to browse slowly from right to left, looking, walking, and unfolding, so that the amount of information could be accumulated bit by bit: from the suburbs to the Rainbow Bridge, the buildings and terraces were stacked up, and all kinds of people appeared one after another, just like a one-shot movie.

In the first section, the suburban landscape is depicted—with low thatched eaves and a crisscross network of country lanes—where figures are seen coming and going. The story begins with a pastoral scene.

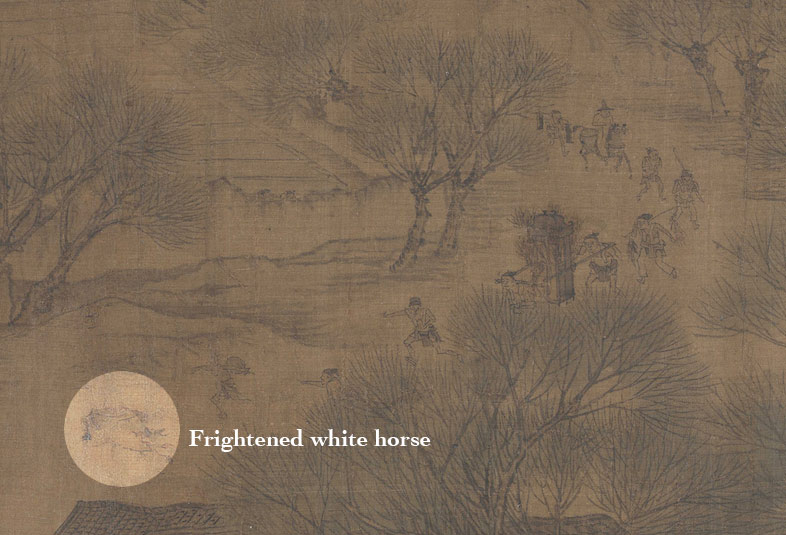

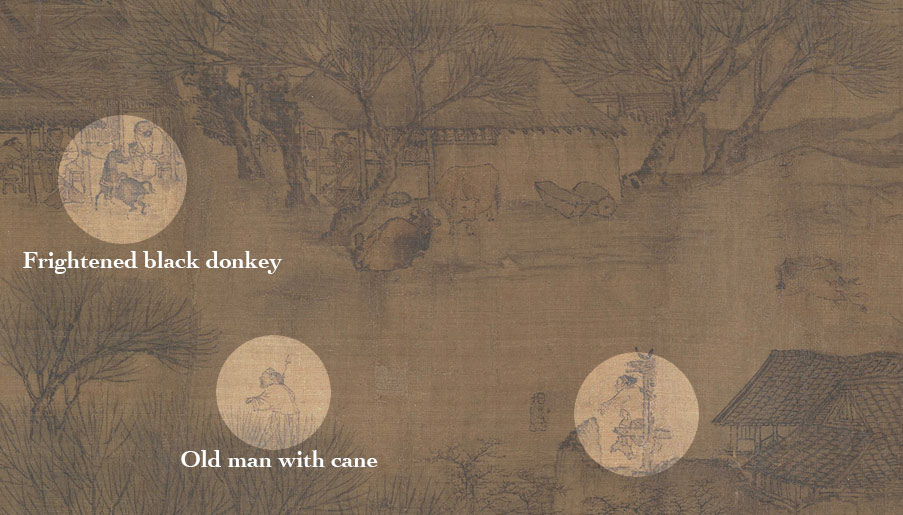

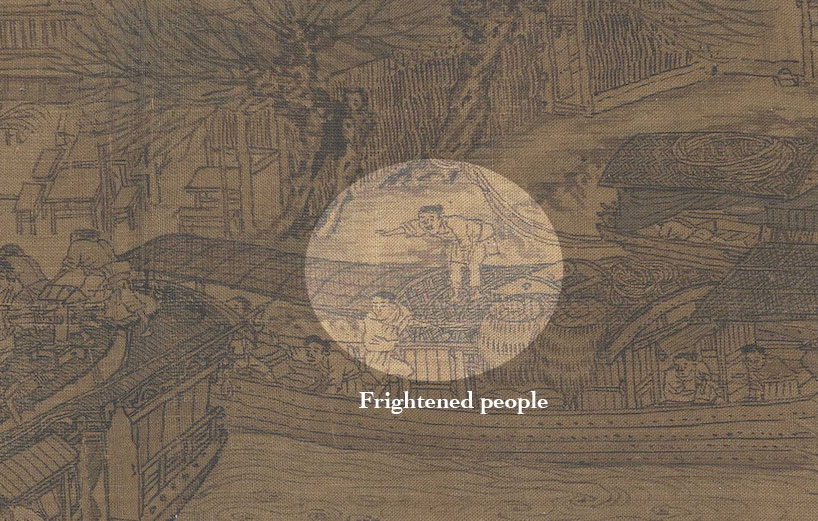

A caravan of homeward-bound visitors appears on the horizon. In the very front, a white horse, its front half marred by injury, bolts in a wild, uncontrolled dash. Two grooms frantically give chase, and panic swiftly ripples through the assembled crowd.

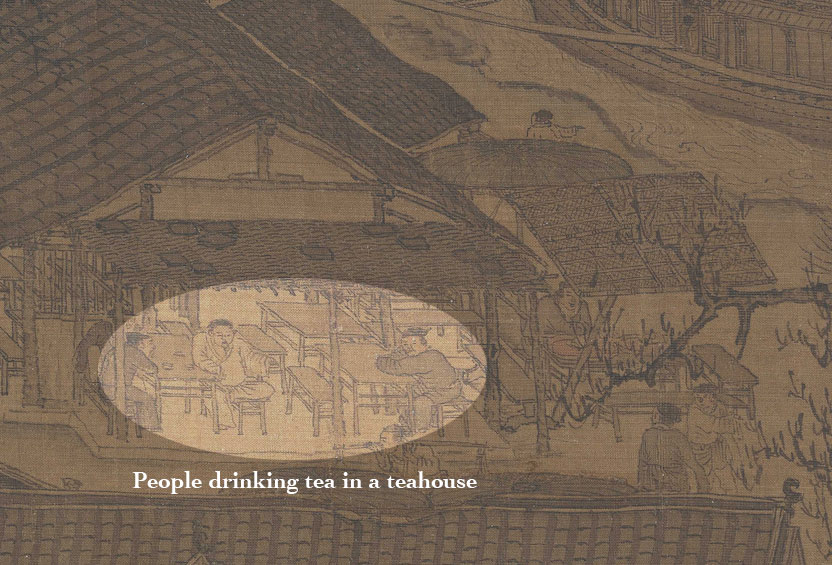

An elderly man urgently signals nearby children to take cover, while two yellow oxen at the roadside twist their heads in alarm. Ahead of the white horse, a black donkey, startled as well, lets out a piercing bray. Diners inside a nearby teahouse glance up in surprise, and an old man with a cane scrambles in desperate haste.

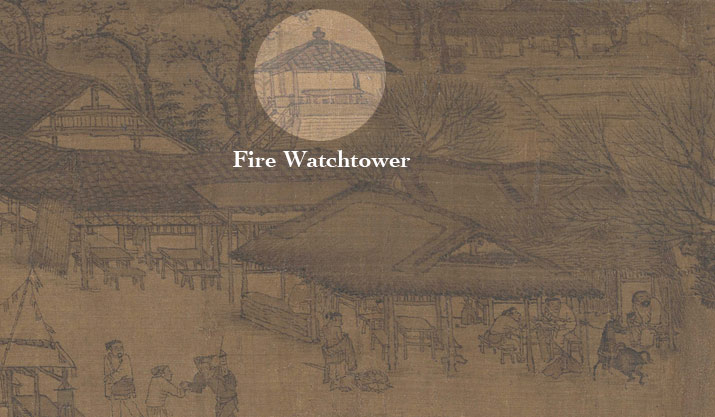

In Bianjing, most structures are built of brick and timber. On the city’s fringe stands a Watchfire Tower—a state security post of the Song dynasty capital, much like today’s fire brigade.

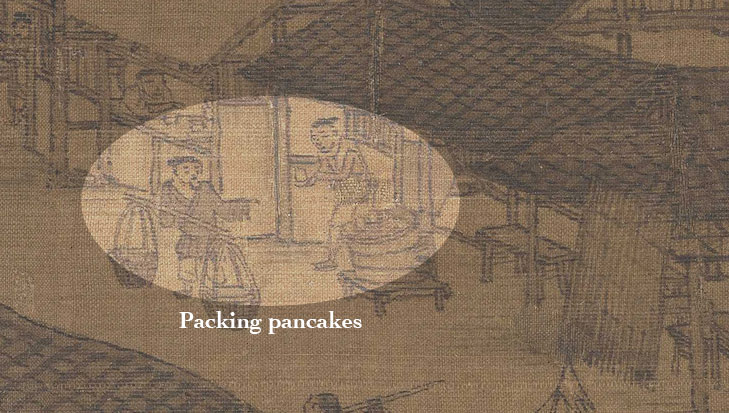

Adjacent to a small eatery, freshly baked, steaming flatbreads have just emerged from the oven as a young attendant hurriedly packages them for passersby.

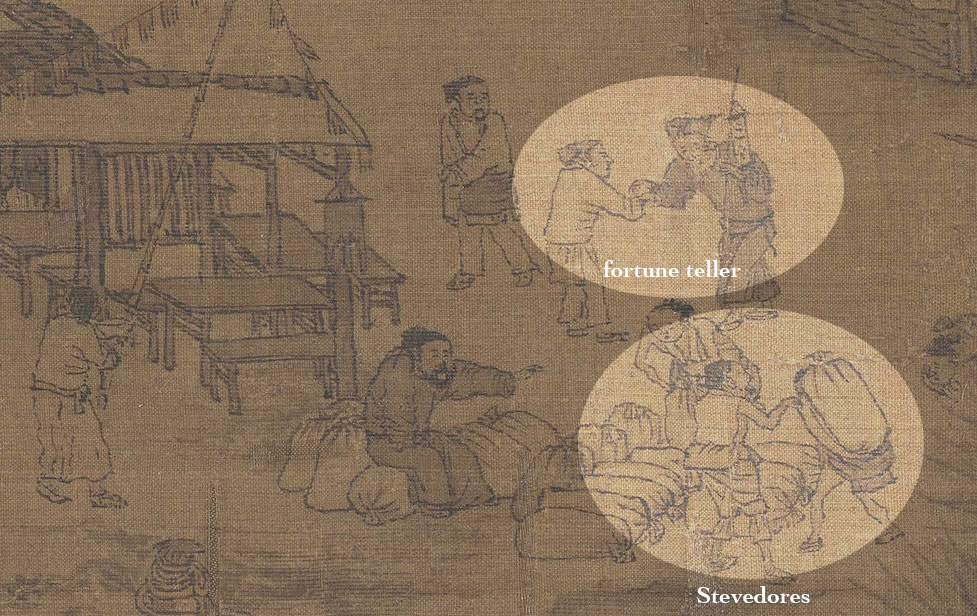

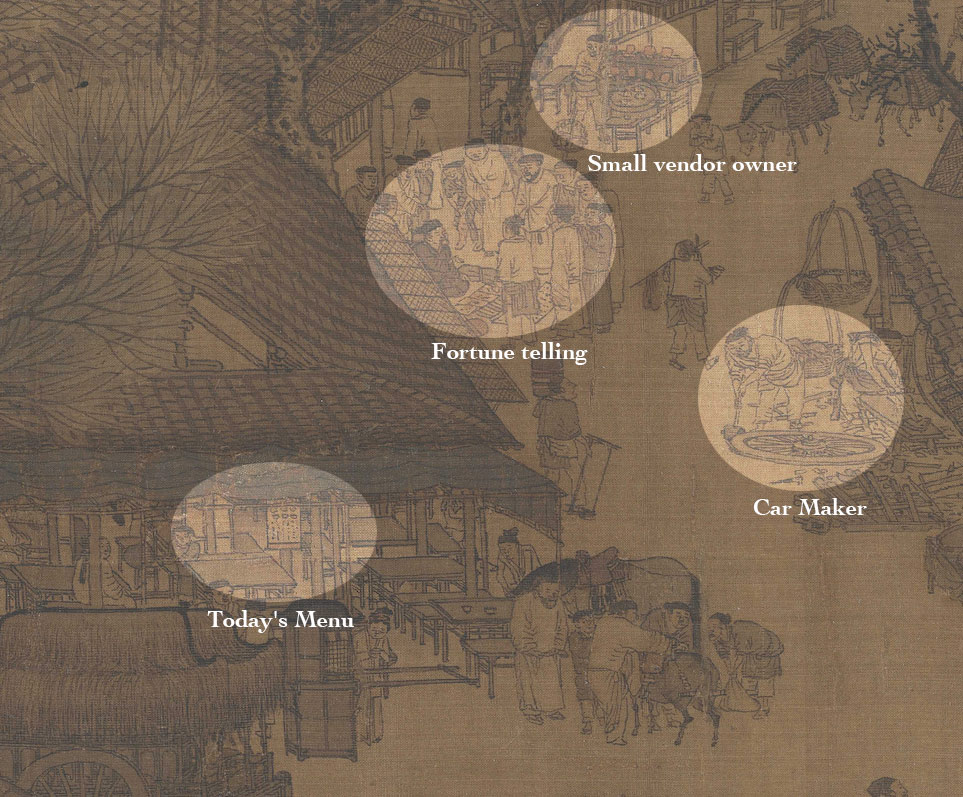

Traveling into the city along the Bian River, restaurant proprietors embellish their storefronts, fortune tellers engage in animated conversations with pedestrians, and dockworkers unload ships.

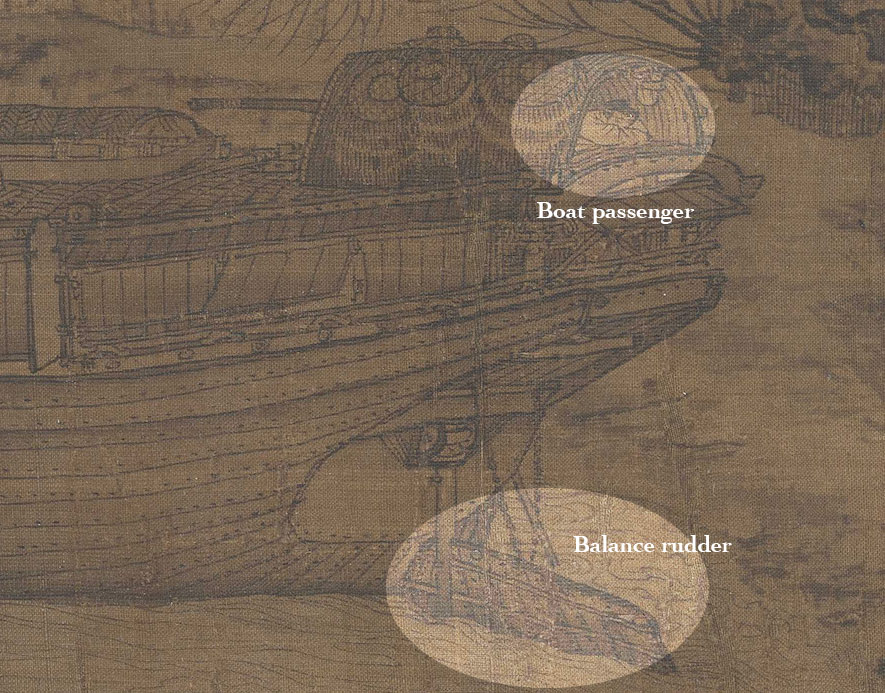

Lining both banks are riverside inns with grand entrances crowned by gracefully upturned eaves and ornate canopies. In one such establishment, a weary boat passenger dozes at the foot of his cot, while the era’s ships, equipped with agile balance rudders, testify to Northern Song shipbuilding’s world-leading innovation.

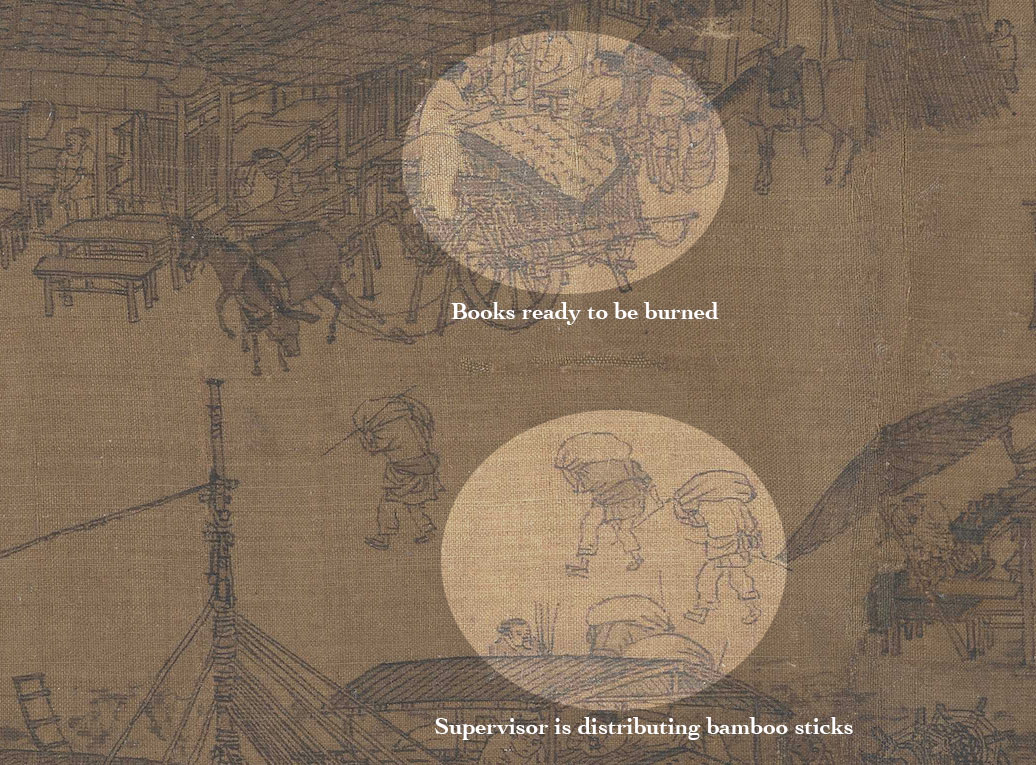

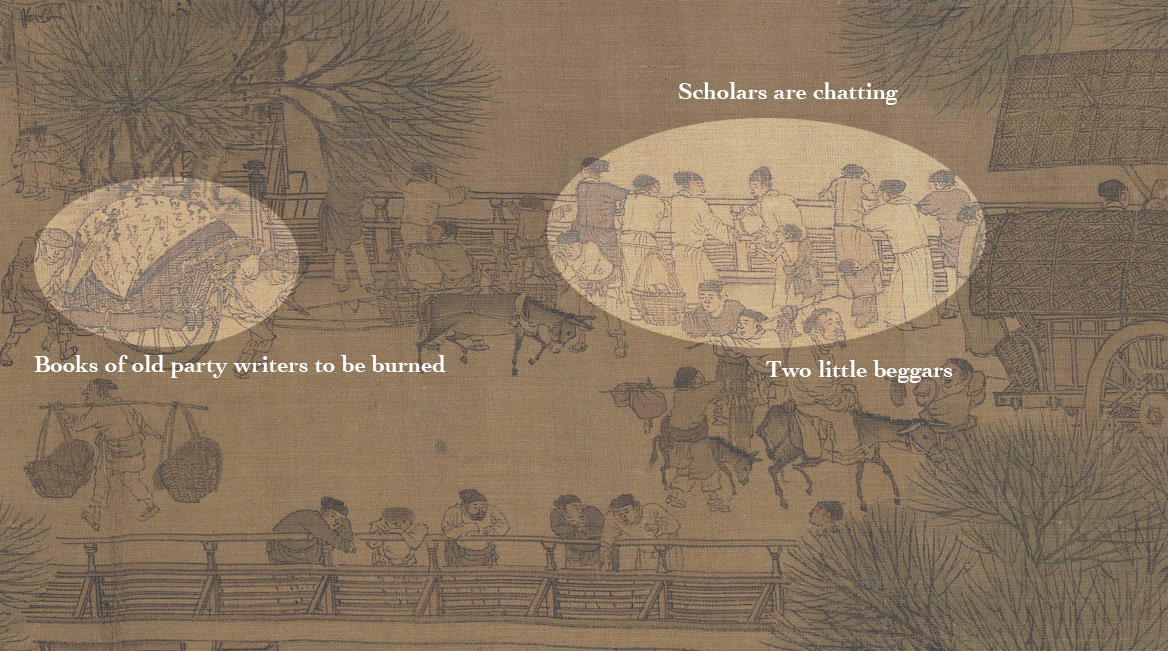

Further along, overseers distribute bamboo tokens to laborers hefting large bundles—a traditional method of piecework payment. The more bundles a laborer carries, the more tokens he earns, and the higher his day’s wage. In the distance, a donkey cart carries a stack of books marked for incineration. Amid the turbulent reform and factional strife of the Northern Song—where new powers clashed violently with the old—these volumes, perhaps containing the precious notes of revered masters, are doomed to the flames by order of Cai Jing, the newly empowered party chief during Emperor Huizong’s reign.

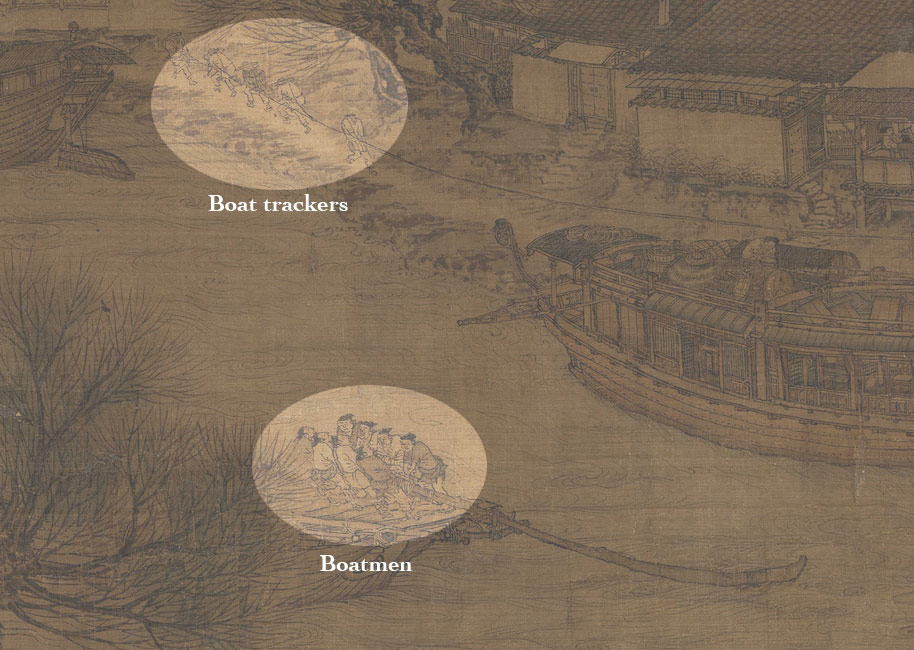

Advancing onward, the river grows increasingly turbulent. On the banks, dockworkers strain with all their might, hauling in heavy ropes; midstream, an elegantly designed double-ended rowboat—crafted to navigate the crowded, busy Bian River—glides through the rapids.

As the river nears the city gate—Bian River being the capital’s vital, life-sustaining artery, carrying more than ten times the cargo of any other waterway—the current abruptly reverses near a treacherous zone known for frequent shipwrecks.

A man aboard a vessel points in terror toward the distance, drawing every eye.

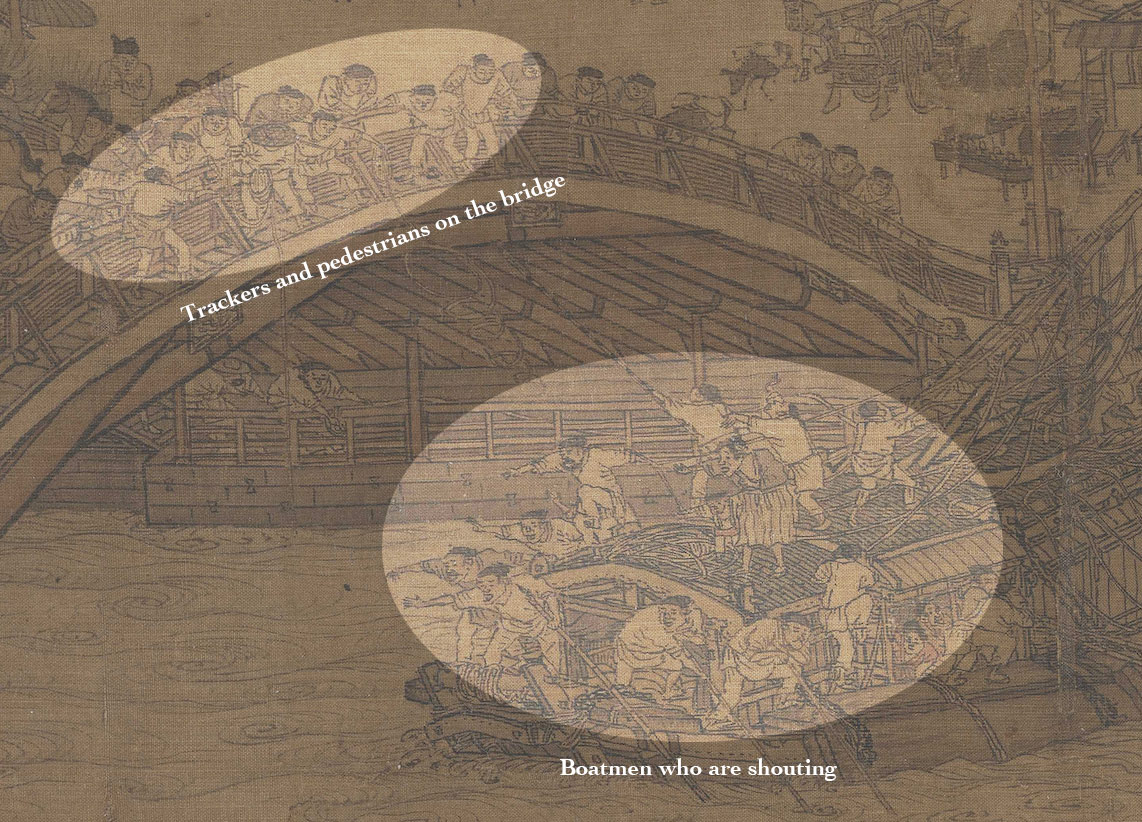

At the very heart of the scene, atop the narrow, swiftly flowing span of the Overlapping Beam Arch Bridge, a crisis unfolds: several dockworkers, absorbed in their toil, fail to signal the sailors to lower the mast. An enormous ship hurtles toward the bridge. Shouts erupt from pedestrians; dockworkers release their ropes as crew members scramble—some seizing the helm, others manning the oars, throwing lines, lowering masts, or propping open the bridge’s narrow portal—in a frenetic ballet of impending disaster. A handful of onlookers even leap over the railing, compelled by both courage and desperation.

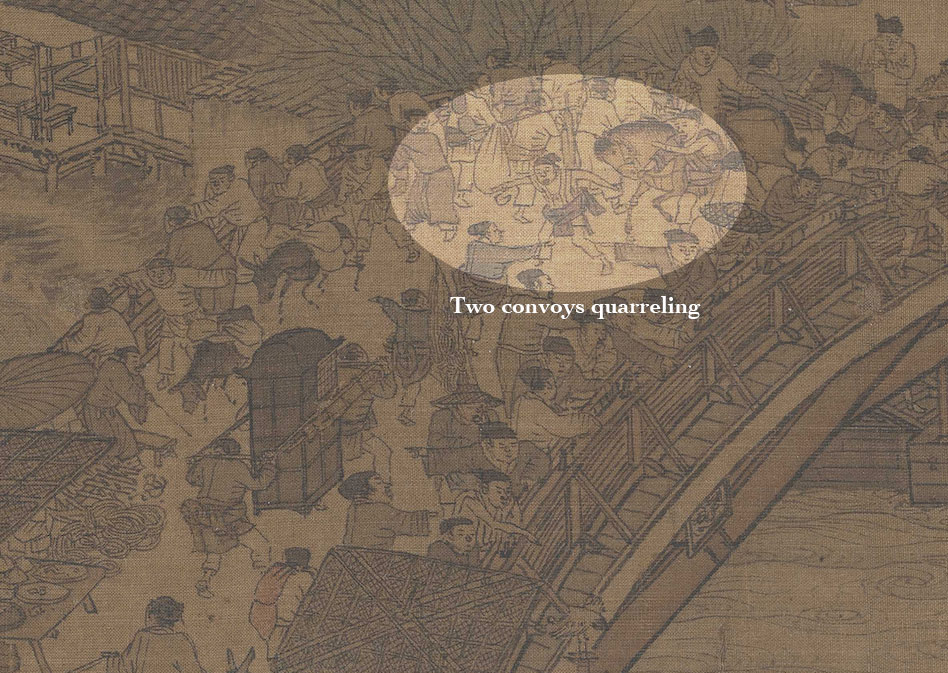

Beneath the perilous bridge, danger lurks, yet above it the scene is even more chaotic. Civil officials in sedan chairs and military officers on horseback square off, their entourages—sedan bearers and grooms alike—strutting with haughty defiance in a cacophonous dispute.

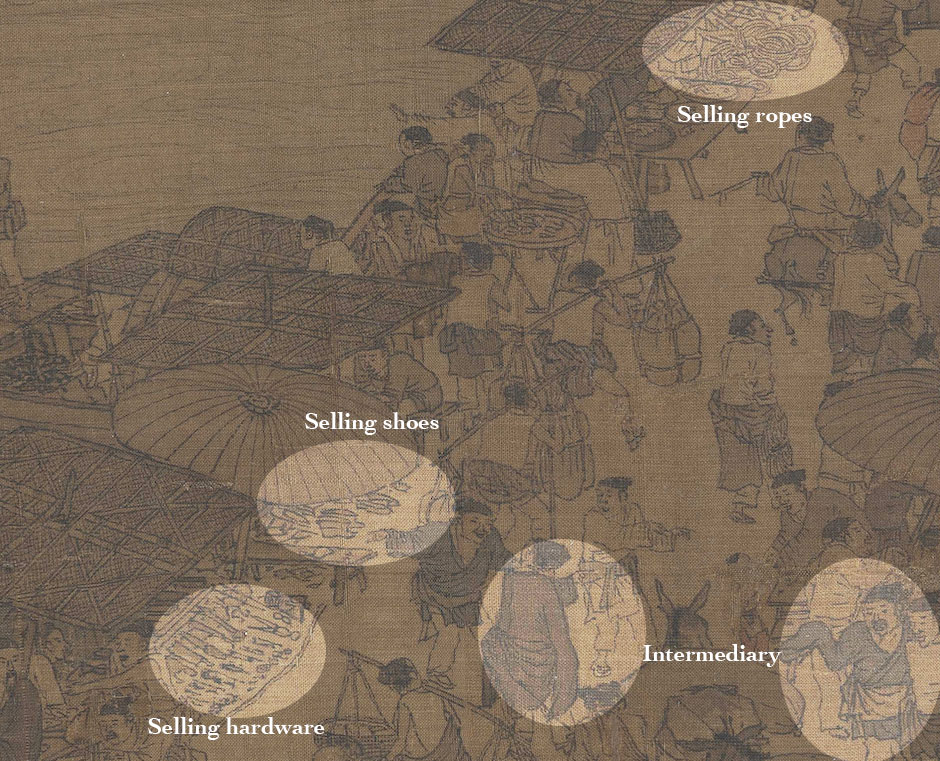

On the crowded bridge, vendors hawk ropes, a myriad of shoes, and iron wares—staking out their small stalls in the very thoroughfare. Despite the narrowness of the bridge, pedestrians, load carriers, and beasts of burden jostle for space, while the street sellers calmly call out their goods. Nearby, two particularly flamboyant figures, known in ancient times as “tooth brokers” (modern-day intermediaries), wear long sleeves designed not for fashion but to discreetly exchange secretive signals and negotiate deals.

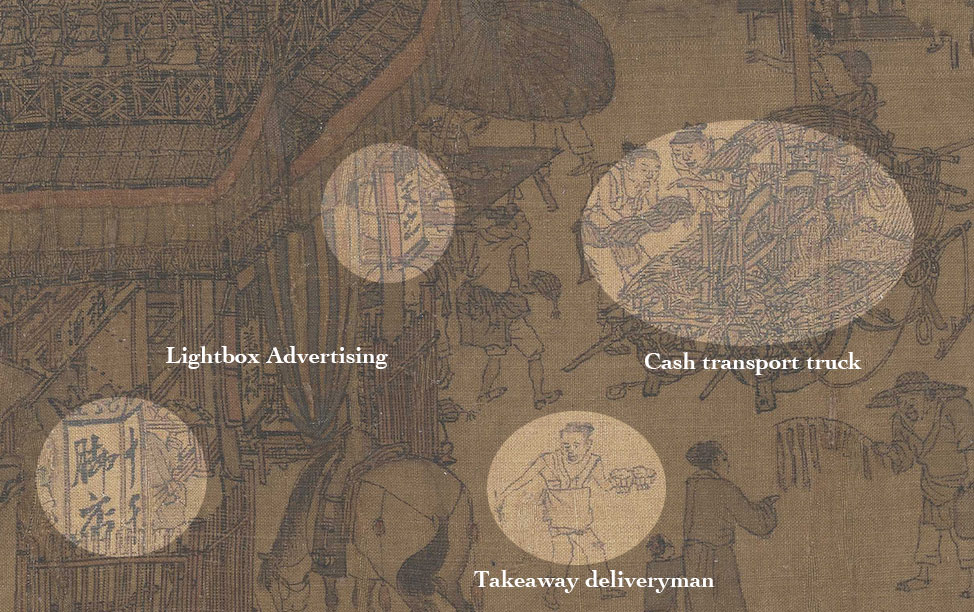

A seemingly humble wooden cart reveals itself to be a money transport vehicle. Two men count heavy copper coins—each a part of the standard 770-qian currency—while another struggles to retrieve the funds from within.

Below, a delivery courier clutches two take-out orders. The culinary scene in Song-era Bianjing is vibrant, with restaurants already offering prompt, on-demand meal services reminiscent of modern delivery.

Nearing the city, beneath the cheerful facade of the “Huan Lou,” a prominent sign advertises the “Ten Thousand Jiao Store”—a name inspired by the phrase “Xin Feng Fine Wine for Ten Thousand Jiao.” A small illuminated advertisement box even offers candle orders for night-time allure, arguably the earliest example of a lit sign.

At a teahouse by the river, locals indulge in tea—a passion of the Song people, with teahouses serving as vibrant social hubs akin to modern cafés. Song tea was categorized into seven distinct types—white leaf, citrus leaf, morning, fine-leaf, Ji tea, evening, and cluster tea—with teahouse names as quirky as “Skull Teahouse,” “Cave of Ghost Tea,” “Street Car Teahouse,” and “Yellow Beaked Soccer Teahouse.”

The bustling commercial street overflows with life. Restaurants display daily menus, fortune tellers provide impromptu readings on the street, and wheelwrights hammer away at their trade along the roadside. In the distance, snack vendors observe the lively spectacle with keen interest. It was in this era that modern dining practices took root: the advent of heat-resistant vegetable oils popularized stir-frying, and with the abolition of curfews, late-night dining emerged. By the time most shops closed at midnight, officials would rise with the dawn, and breakfast vendors began their day, rendering Bianliang a city that truly never slept.

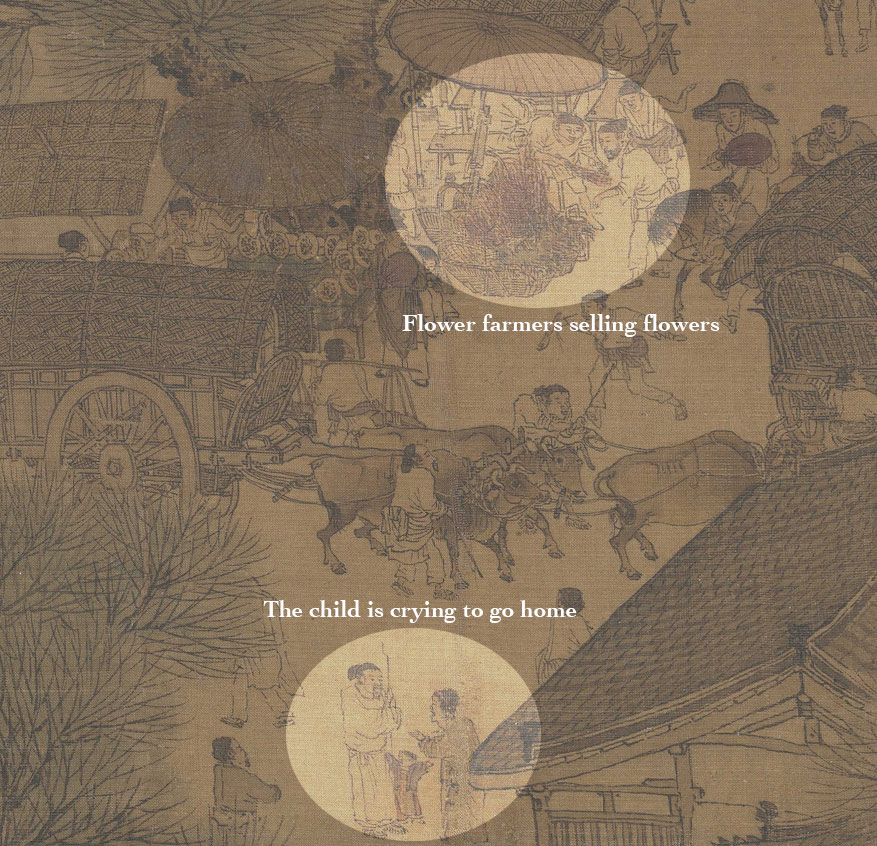

Nearby, a florist displays vibrant flower seedlings to potential middle-class customers, evoking a refined lifestyle. Meanwhile, a small child, wearied by the endless adult socializing, demands to leave the noisy scene behind.

On a modest bridge outside the city, a group of scholarly men idly lean against the railings, watching fish swim by. At the same time, a pair of persistent little beggars clings to a few passersby, determined in their solicitation. In the background, a donkey cart laden with works of the old faction drags on—its cargo destined for the outskirts, where the texts are to be burned.

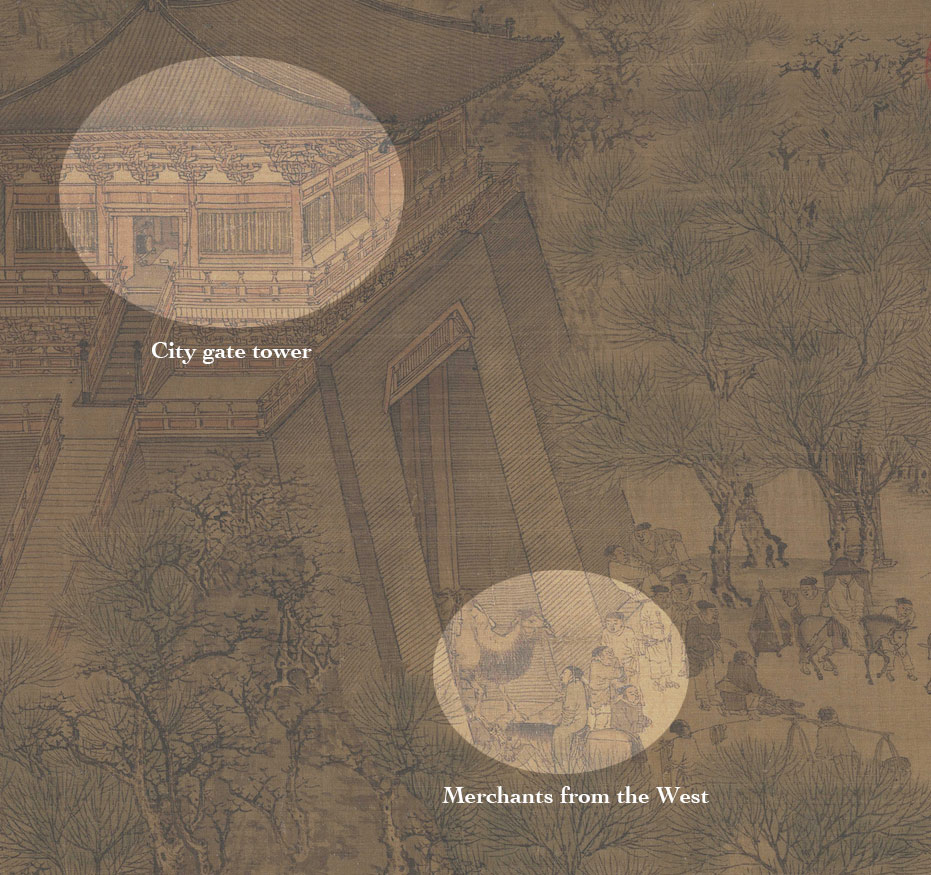

The sprawling metropolis of Northern Song Bianliang, with a population exceeding one million, is encircled by towering, majestic walls. Amidst the bustling streets, foreigners with Central Asian features lead camels through the city—a vivid reminder that even then, global trade was already in full swing.

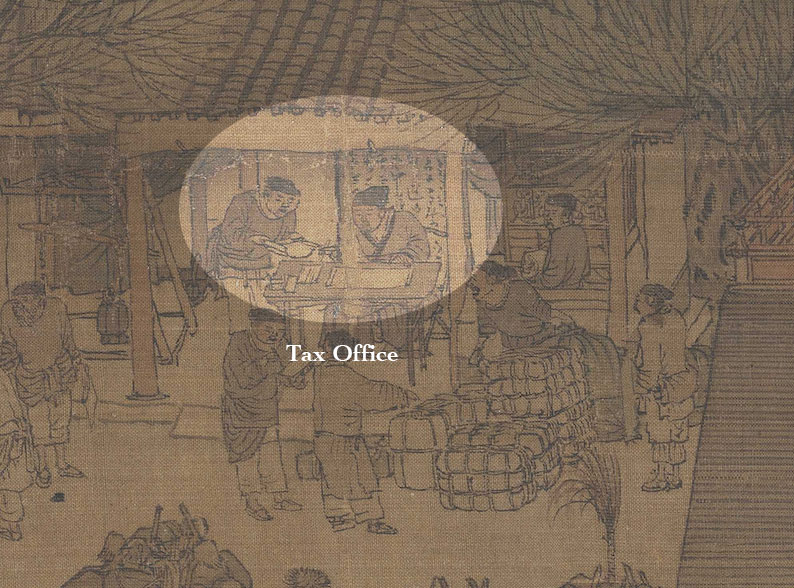

Upon entering the city, every newcomer must first pay taxes. The very first establishment is a tax office where four drivers, burdened with a sack of textiles, find themselves embroiled in a heated dispute with tax officials.

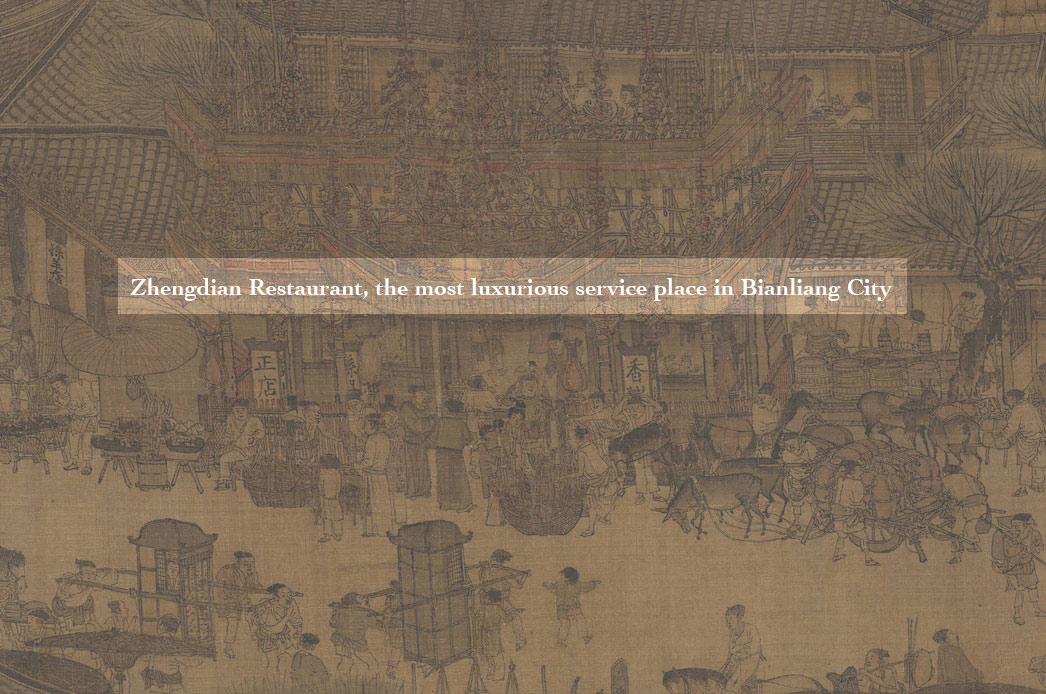

The main restaurant—a high-end tavern—stands as the epitome of Bianliang’s most fashionable, opulent, and indulgent locales. Red gardenia lanterns hang at the entrance, subtly inviting customers to seek pleasures within. In the Song dynasty, red-light districts were neither prohibited nor hidden; brothels dotted the streets, catering to both official and private courtesans, with legendary figures such as Li Shishi gracing the night.

The “Sunyang Store” specializes in mutton—a luxurious commodity at the time. In the shop, a butcher skillfully cleaves meat on a heavy slab while a young apprentice diligently sharpens his knife. Just outside, a bearded street performer captivates an eager circle of listeners with enthralling tales drawn from history, finance, mystery, and the supernatural—the era’s most popular form of entertainment.

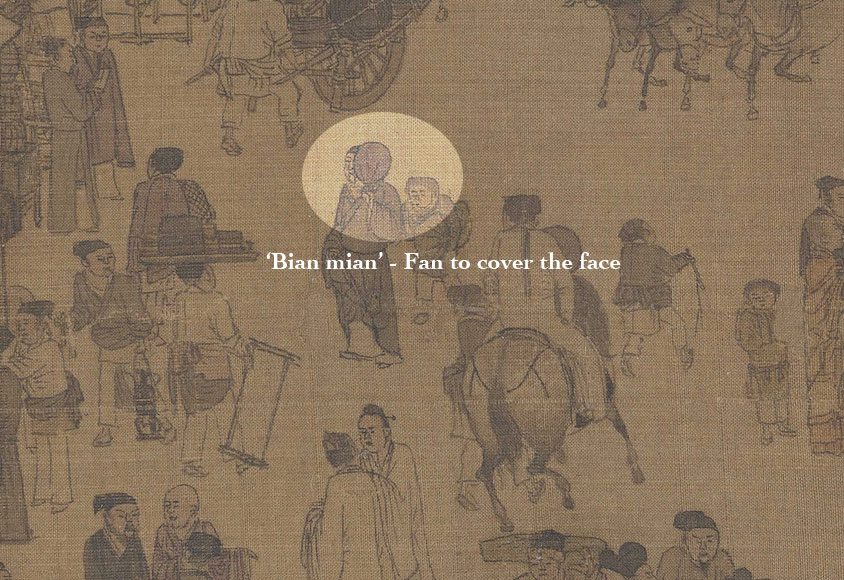

A subtle social gesture known as “Bian Mian” is captured on screen: a person uses a fan to obscure their face when encountering an unwelcome acquaintance on the street—a courteous, almost ritualistic move reminiscent of today’s tendency to hide behind smartphones in awkward moments.

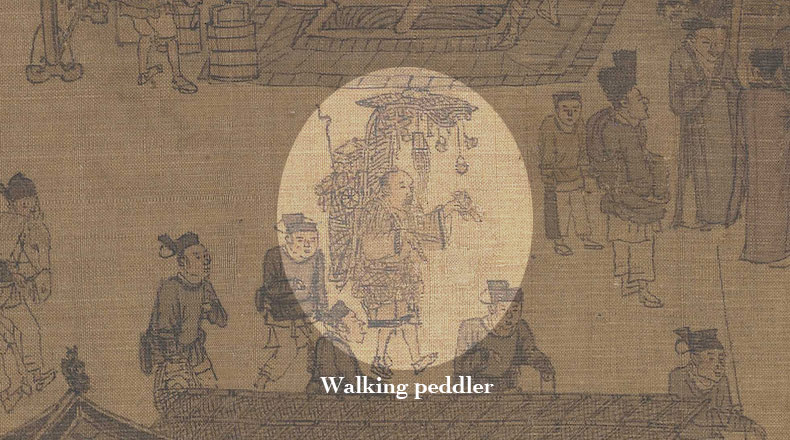

On the street, a peddler walks with his goods on his shoulder, shaking a small rattle drum in his hand, and singing melodiously, introducing the styles and uses of the goods, and trying hard to sell them, in order to attract customers who are mainly women and children.

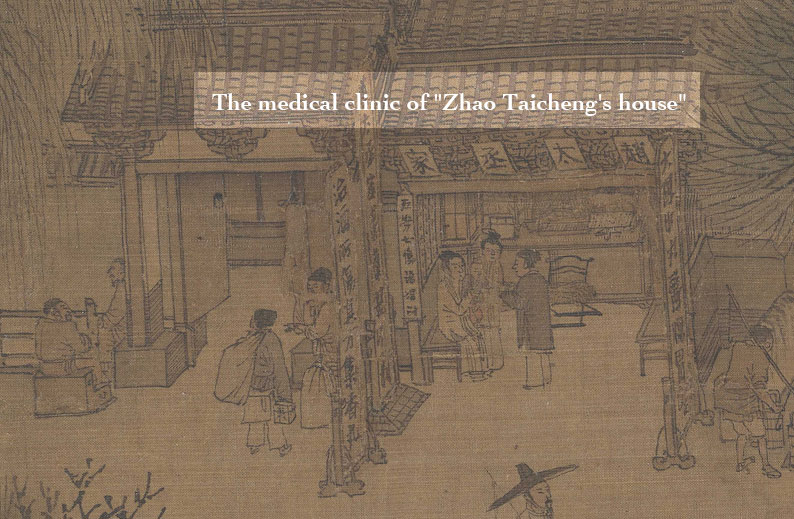

This is the apothecary of “Zhao Taicheng’s Household,” the sole official residence depicted in the scene. Its owner, likely a retired imperial physician of at least the sixth rank, serves local patrons. Inside, two women, cradling their children, wait patiently for their turn.

“Along the River During the Qingming Festival” is a grand, richly detailed traditional Chinese painting that captures the urban panorama of Kaifeng, the Song dynasty capital. Its vivid portrayal of bustling streets, diverse trades, and intricate cultural details offers an immersive glimpse into the era’s economic vitality, social complexity, and cultural richness—making the scroll a timeless emblem of artistic and historical exchange.

Here I also recommend you to take a look at the most famous copy, “Along the River During the Qingming Festival” by Qiu Ying from the Ming Dynasty.

-full.webp)

-full.webp)

-full.webp)

(c. 1883)-full.webp)

-full.webp)

-full.webp)