This world-famous masterpiece of social customs painting of the Northern Song Dynasty has spawned countless copies, imitations, different versions and re-creations. Among them, Ming Dynasty’s Qiu Ying’s “Along the River During the Qingming Festival” is the most famous. The number of copies is countless. Various versions of “Along the River During the Qingming Festival” have circulated in China and around the world. Their wide dissemination and far-reaching influence are rare in the history of Chinese painting and even in the history of world art.

The two paintings have many similar contents and plots, reflecting the inheritance of history, but the artistic expression methods are different; there are many additions to the handicraft and commercial trades in Qiu Ying’s version, reflecting the development and evolution of history and the unique prosperous economic form of Suzhou. The two paintings have the characteristics of different times and regions in the description of social customs and lifestyle details.

Qiu Ying’s version is not a simple repetition of Zhang Zeduan’s version. The two paintings are independent original works. Qiu Ying’s “Along the River During the Qingming Festival” (Xinchou version) follows the pattern of Zhang Zeduan’s “Along the River During the Qingming Festival” in terms of overall composition, that is, the pattern of suburbs-Hongqiao-outside the city-city streets, but adds the palace garden part, which may be the original ending of Zhang Zeduan’s “Along the River During the Qingming Festival”.

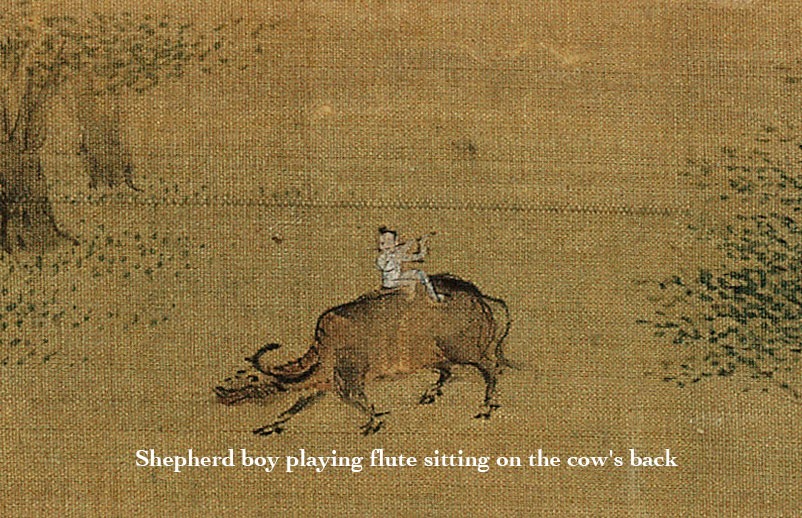

During the Qingming Festival, Suzhou becomes the perfect canvas for spring outings. People flock outdoors to bask in the gentle pleasures of the season. In the scene, a shepherd boy rides a sturdy ox while his pastoral flute sings, its notes interweaving with the murmuring stream and the tender blossoms of willows and peach trees.

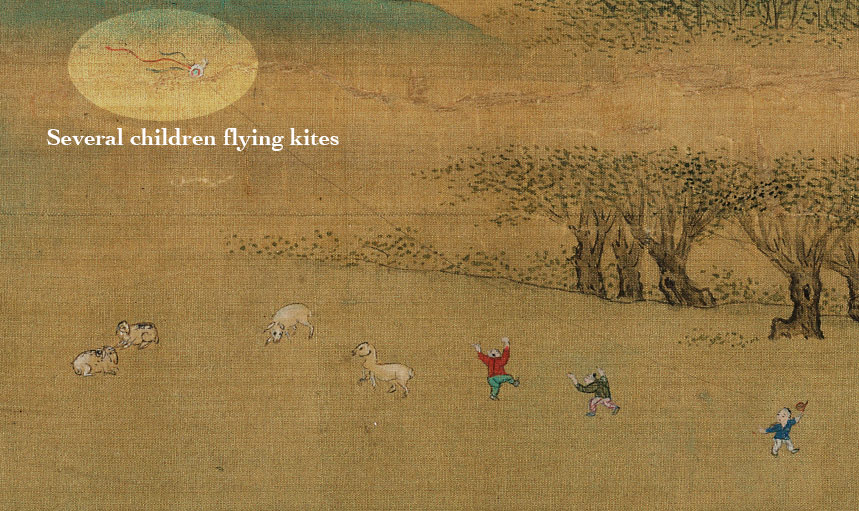

Nearby, several children joyfully fly kites across the countryside—a vivid portrayal of lush, verdant landscapes that capture the essence of Zhang Jiuling’s Tang verse: “Orchid leaves flourish in spring; osmanthus blossoms shine in autumn. Life itself rejoices, making every season a festival.”

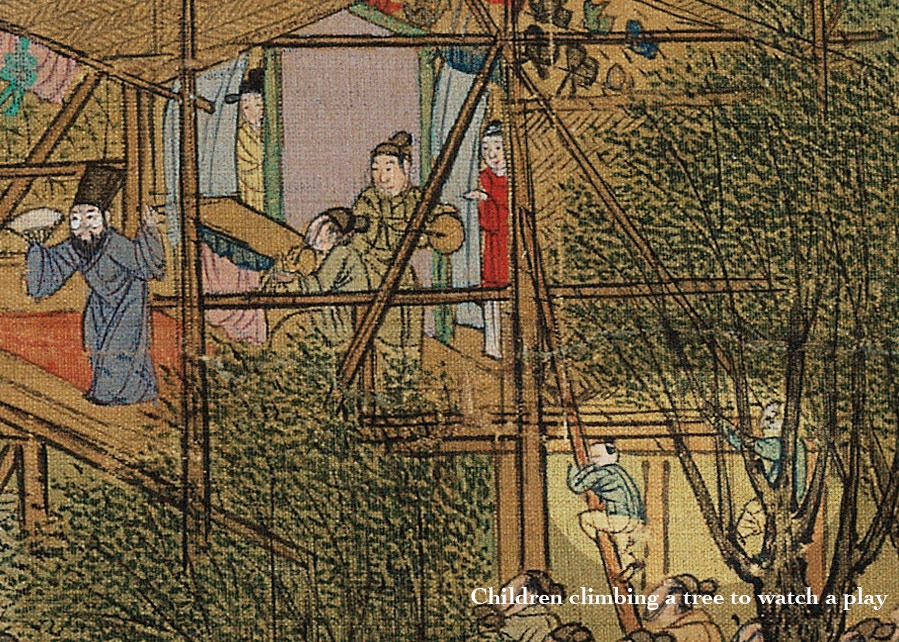

An ancient Chinese drama unfolds on stage, drawing a rapt audience. The spring opera is in full swing, its vibrant energy echoing the verses of Qing Gu Lu’s “Qing Jia Lu – Spring Stage Drama”: “In the heart of February and March, chivalrous figures erect stages in the open fields, pooling their funds for a performance that gathers both men and women—an event to invoke agricultural fortune.” The Qing poet Cai Yun also mused, “A thousand household torches do not chill the wind, and even in ten li of fragrant dust, the rain remains dry. Once the lamps are dimmed, the spring stage drama commences, luring idle souls to the open fields.”

For children, the theater is pure delight—an all-in-one feast of play, food, and spectacle. In one playful moment, a few agile youngsters have clambered up a tree to get a better view of the performance.

Set against a backdrop of blue mountains and meandering streams adorned with willows and peach blossoms, a caravan of merchants navigates the rugged mountain paths. The caravan’s master rides a light brown horse with a striking red saddle pad, while his retinue—laden with bundles, backpacks, and parcels—moves through the valley in a dynamic procession, each figure a moving portrait of determined purpose.

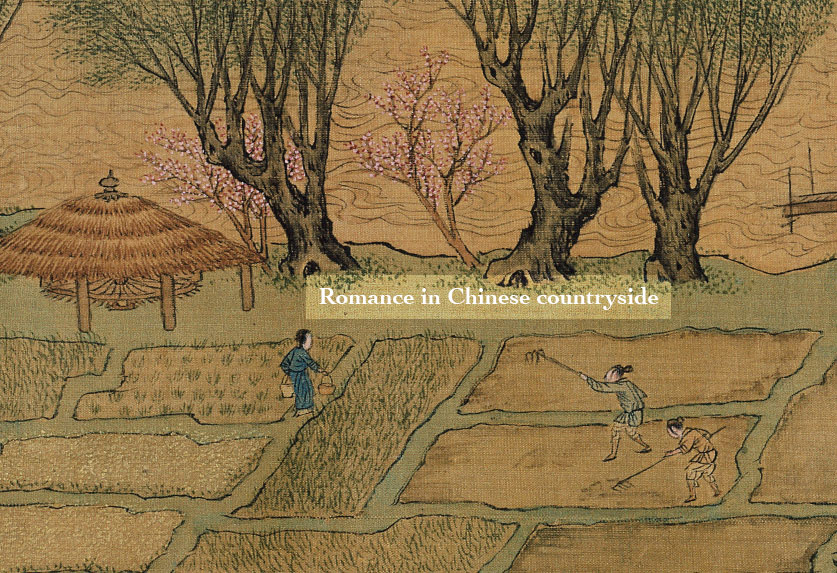

By the riverbank, a humble thatched cottage and a waterwheel punctuate the pastoral scene. Two men labor in the fields, while a woman bearing a lunch basket calls out in a warm, inviting tone, urging them to pause and rest amid the blooming peach blossoms—a tableau of idyllic rural romance.

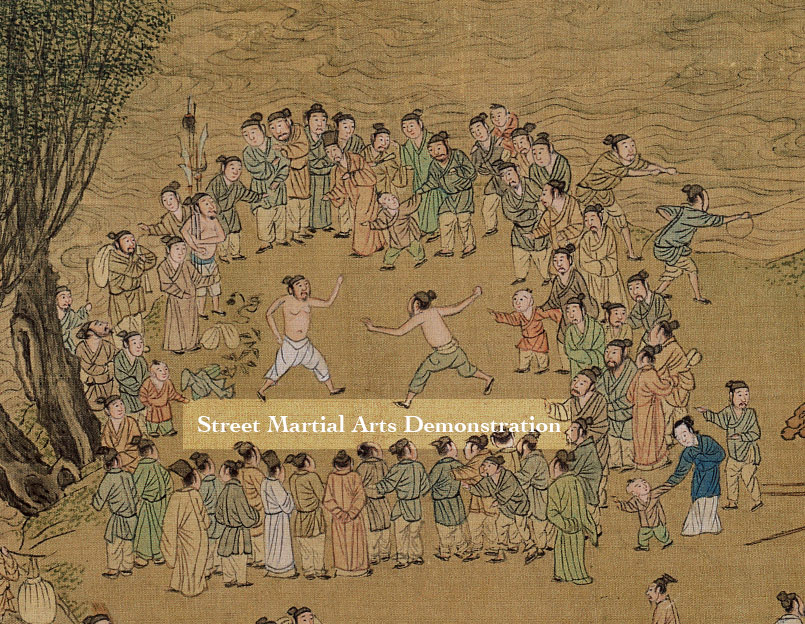

On a bustling street, two bare-chested martial fighters engage in a spirited duel, their performance drawing a captivated circle of onlookers. As the contest concludes, the audience dispenses generous tips, a tribute to the fighters’ strenuous effort and dazzling display.

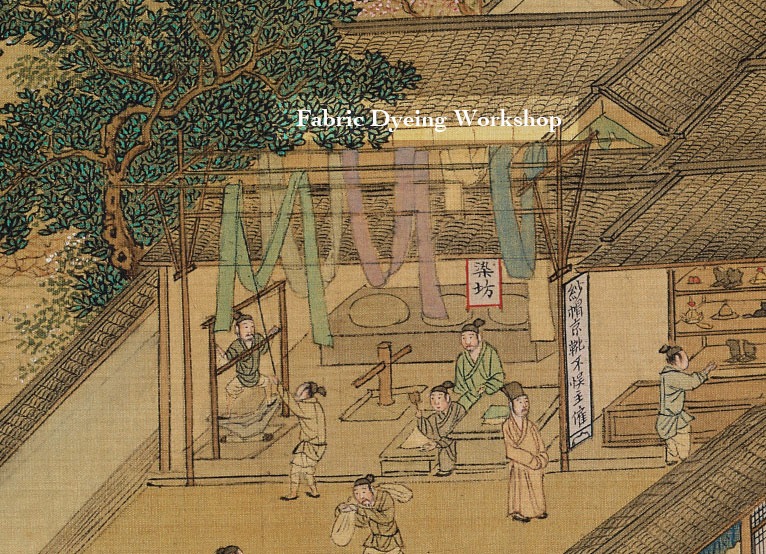

At a combined storefront and workshop, a fabric dyeing establishment reveals its intricate craft. An elder, likely the master dyer, sits at a table by the entrance. Inside, three large dye vats are in operation: water is first brought to a boil, then blended with precise doses of dye and stirred with a wooden rod until a uniform color emerges. The cloth is immersed in this vibrant bath until fully saturated, then removed and allowed to cool. At the center of the workshop, a wooden post with a horizontal beam serves as the frame on which the cloth, once twisted into a “U” shape, is hung. Workers then rotate the cloth from both ends to wring it dry. This meticulous process—applied to silk, cotton, and other fabrics—continues with the cloth being pounded on a stone board with a mallet, a final step known as “brightening the cloth,” reminiscent of modern ironing.

Zhang Zeduan’s “Along the River During the Qingming Festival“ and Qiu Ying’s “Along the River During the Qingming Festival” are two quintessential masterpieces of realist genre painting in Chinese art history. Delving deeply into these works—decoding the historical narratives they encapsulate and unearthing their profound intellectual, historical, and artistic values—is both a fascinating and heartwarming journey.

-2.jpg)