Landscape

From serene countrysides to dramatic seascapes, our landscape collection captures nature’s changing moods in brushstroke and light. These works are not just views, but windows into atmosphere, memory, and the sublime.

-

Claude Monet Water Lilies.

Monet’s radical “broken color” approach—applying pure pigments in rapid, unblended strokes—achieved unprecedented luminosity.

-

Irises (1889): Van Gogh’s Dance with Chaos and Grace

Painted during Vincent van Gogh’s voluntary stay at the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole asylum in 1889, this canvas pulses with raw energy, yet whispers of fragile control.

-

Snow Mountain and Red Trees Scroll, Six Dynasties

A scholar contemplates the vista from a pavilion, while a visitor on a donkey crosses a frost-laden bridge, their postures subtly conveying winter’s bite and literati resilience

-

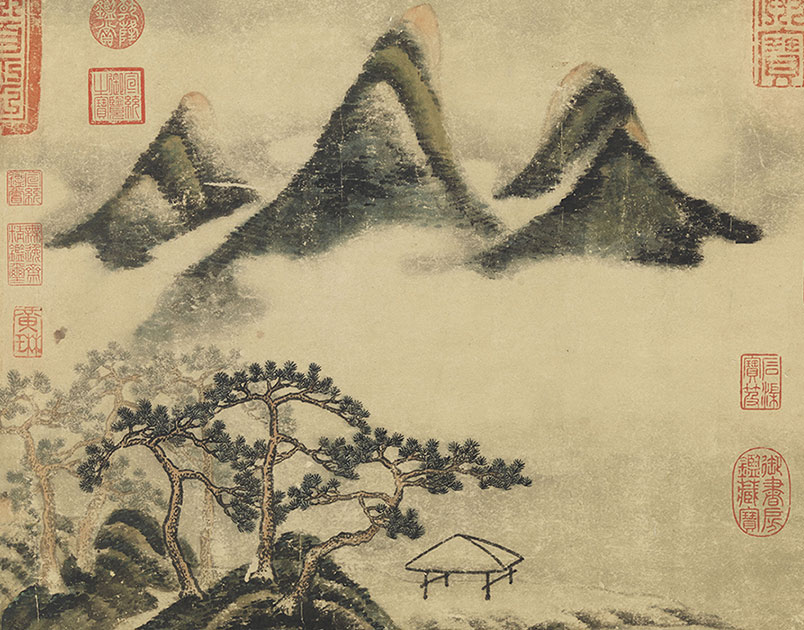

Snow Scenery Scroll. Song Dynasty. Ma Yuan

This work bridges Southern Song lyrical minimalism and Ming reinterpretations, offering insights into Ma Yuan’s enduring influence and the evolution of “academy-style” landscape painting.

-

Spring Mountains and Auspicious Pines Scroll

Mi Fu’s “Cloudy Peaks and Pines” scroll whispers ancient burnout remedies through ink-wash poetry. The lone pavilion stands like a medieval mindfulness app icon, while mist-shrouded pines encode Song-era work-life balance wisdom.

-

Scroll Painting of Chongyang Wind and Rain

Chrysanthemums bloom in abundance, while slanting wind and drizzle animate the scene.

-

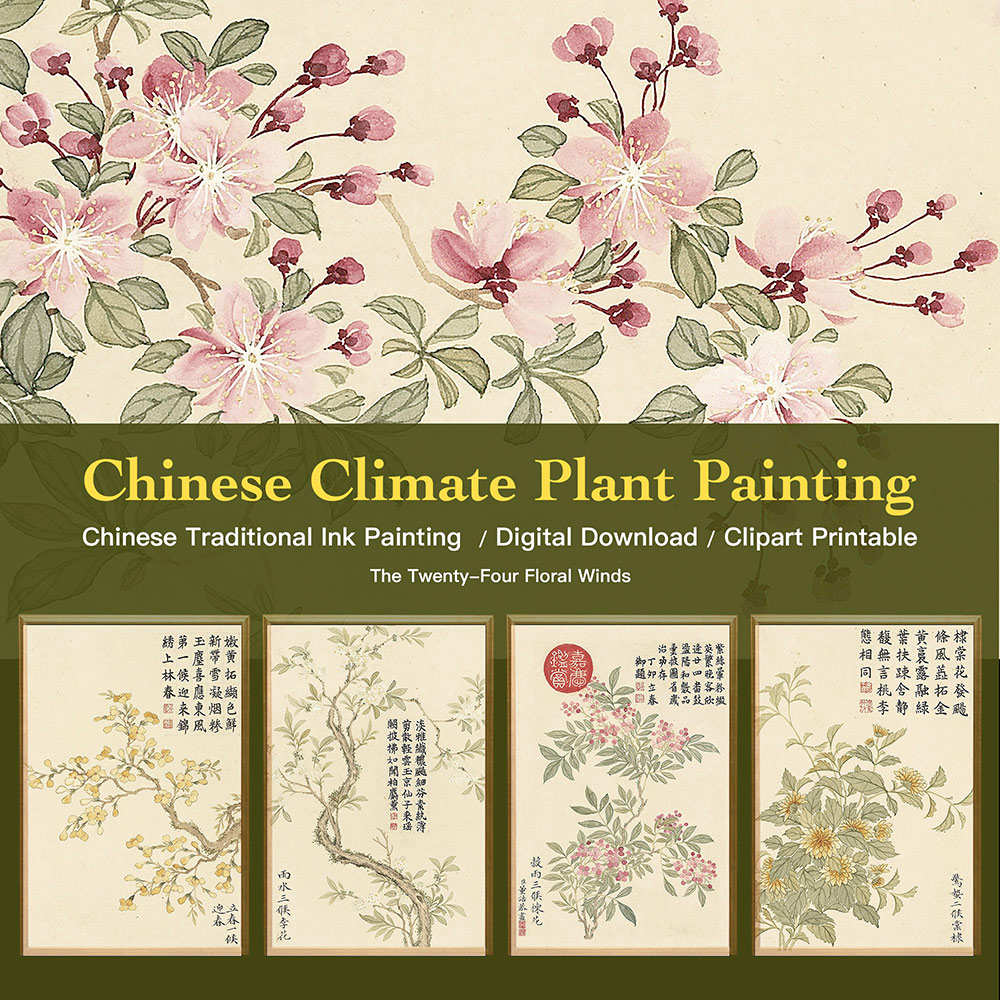

Time-Travel Through Petals: The 2,000-Year-Old Art of Reading Nature’s Clock in Chinese Paintings

“Flower-Signal Wind” refers to the seasonal breeze that brings the message of blooming flowers. According to the traditional Chinese calendar, the period from Lesser Cold to Grain Rain comprises eight solar terms over four months. For each segment, a flower that most accurately embodies its blooming season is chosen to symbolize the “Flower-Signal Wind.

-

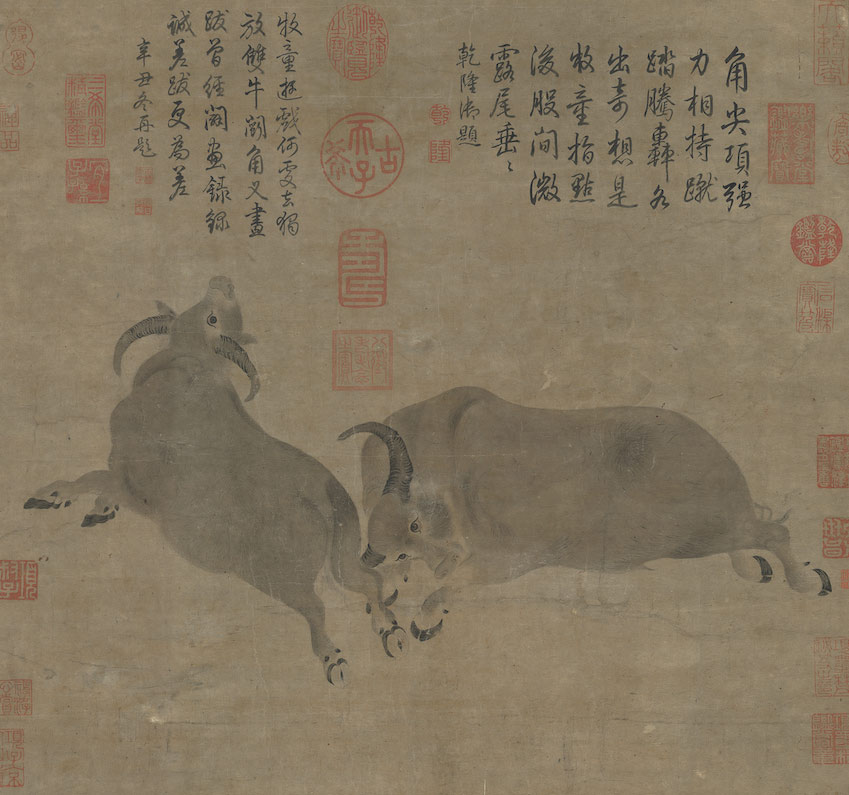

Roaring Strength on Paper: Experience the Intensity of Dai Song’s Tang Dynasty Bullfight

The bulls are portrayed with robust, muscular forms and a palpable vitality, evoking an impression of raw power that seems capable of overwhelming multitudes.