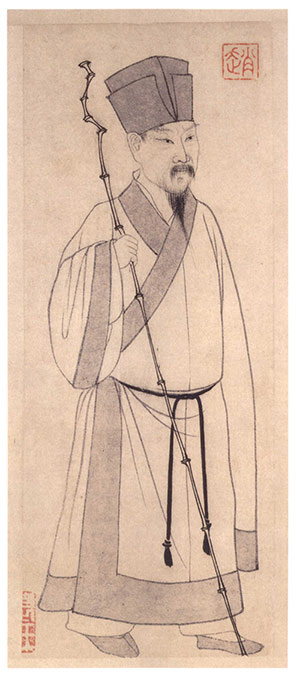

About the Artist

Complete Handscroll Image

-

Scroll left or right to view more

Artwork Story

“Cold Food Observance Scroll” (Hanshi Tie)

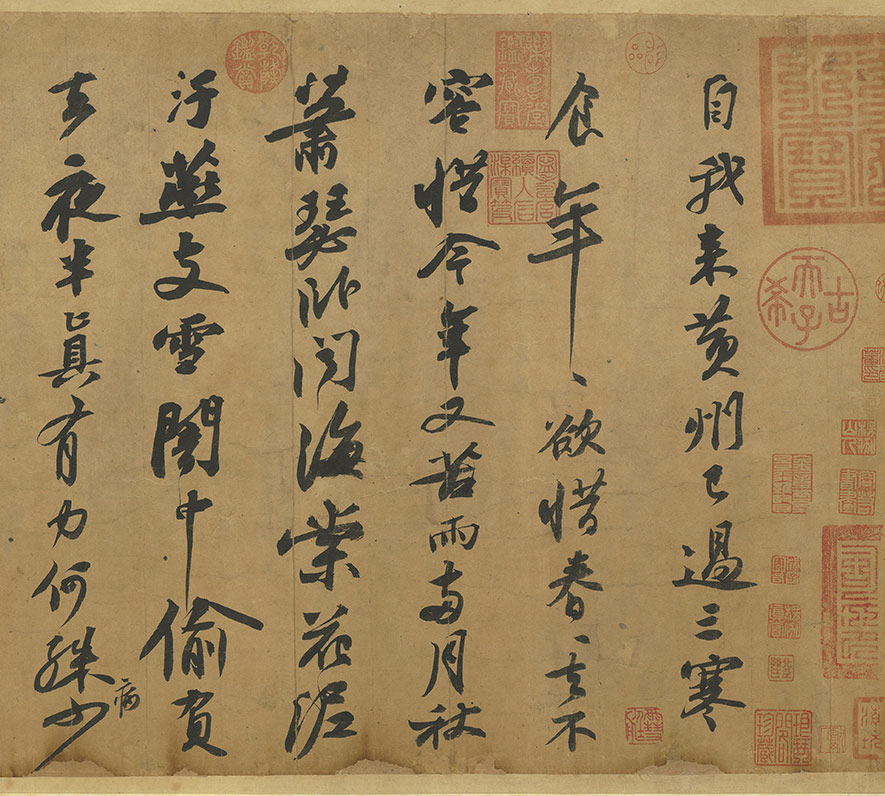

This iconic calligraphic masterpiece was created by Su Shi (Su Dongpo) in April 1082 (Yuanfeng 5th year), three years after his exile to Huangzhou. Composed during the Cold Food Festival, the two poems express his reflections on seasonal changes, personal hardships, and career setbacks following the infamous Crow Terrace Poetry Case. The text, later transcribed into this scroll, reveals Su Shi’s emotional turbulence through dynamic, free-flowing brushwork—characters grow larger and more unrestrained as his anguish intensifies.

Despite lacking formal training in suspended-wrist technique, Su Shi pioneered a deeply personal style: bold, vigorous brushstrokes with broad structure and dense, lacquer-like ink tones, redefining calligraphy as a medium of emotional expression. The scroll bears Huang Tingjian’s postscript, who praised it as “Su Dongpo’s supreme surviving work.”

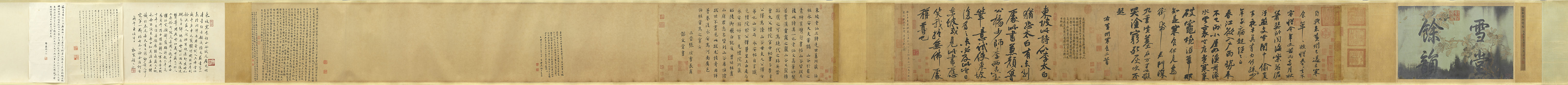

Miraculously preserved through centuries of disasters, the scroll survived multiple fires—its paper scorched yet text intact. After escaping the looting of the Old Summer Palace during the 1860 Anglo-French invasion, it passed through private collectors. In 1922, Japanese collector Kikuchi Seidō acquired it, only to rescue it from flames during the 1923 Great Kantō Earthquake, leaving smoke stains but sparing the script. It endured WWII’s Tokyo firebombings unscathed and was later repatriated to Taiwan. Now housed in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, this “scroll of miracles” stands as a testament to artistic genius and historical resilience.

Huangzhou Cold Food Poems (黄州寒食诗) was composed in the fifth year of the Yuanfeng era (1082), with the calligraphy likely completed shortly thereafter. The poems vividly express Su Shi’s (Su Dongpo) grief and indignation during his exile in Huangzhou, and the brushwork dynamically mirrors the emotional cadence of the text. In the running-cursive script, characters vary freely in size and proportion—Su himself described his calligraphy as “short, long, plump, or lean, each with its own vitality”. This scroll exemplifies his philosophy through its deliberate interplay of character scales and spatial arrangements.

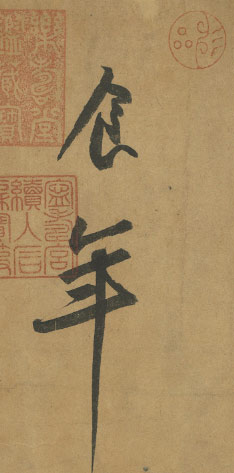

Notably, characters like 「年」 (year), 「中」 (middle), 「葦」 (reed), and 「紙」 (paper) feature elongated vertical strokes in their final strokes. These bold, descending lines disrupt the compositional balance while paradoxically unifying the piece’s rhythm. For instance, the towering vertical in 「年」 anchors the opening line, its weight symbolizing the burden of time, whereas the jagged slant of 「破竈燒濕葦」 (burning damp reeds in a broken stove) visually echoes the text’s despair.

Su’s mastery lies in his ability to orchestrate contrast: compact clusters of small characters (e.g., 「小屋如漁舟」—”my hut sways like a fishing boat”) juxtapose with expansive, sweeping forms (e.g., 「死灰吹不起」—”cold ashes refuse to reignite”), creating a visual tension that mirrors his emotional turmoil. The scroll’s spatial composition (bubai 布白) transcends mere aesthetics, becoming a cartography of the poet’s psyche—where ink and void converse like lamentations and silences.

(c. 1380-1390)-full.webp)

-full.webp)

-full.webp)

-full.webp)

-full.webp)

-full.webp)