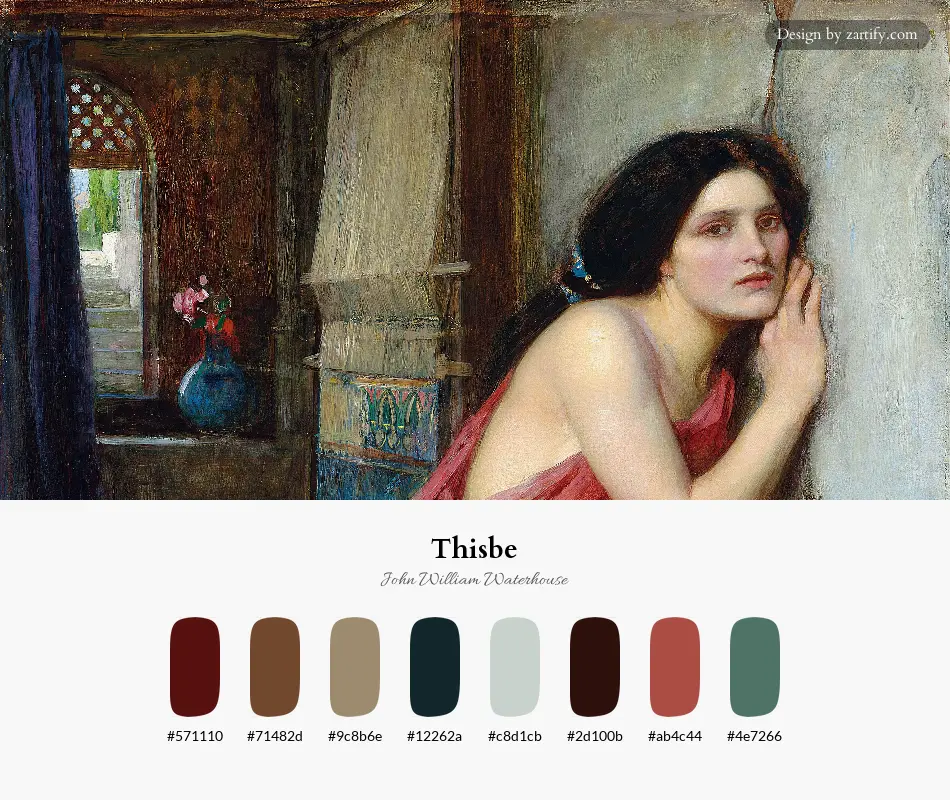

About the Artist

Master’s Palette

Reveal the unique color story behind each piece, helping you delve into the artistic essence, and spark boundless inspiration and imagination.

Bring the captivating colors to your project. Click to copy!

Artwork Story

John William Waterhouse’s Thisbe plunges us straight into the tragic heart of Ovid’s myth, where love and miscommunication collide with bloody consequences. The painting, though part of a private collection and less frequently exhibited than some of his other works, carries that unmistakable Waterhouse signature—lush fabrics, a dreamy yet tense atmosphere, and figures caught mid-motion like actors on a stage. Thisbe, her pale limbs draped in gauzy fabric, seems to hover between life and death, her outstretched arm both reaching for and recoiling from the fate that’s already found her. Waterhouse, ever the dramatist, doesn’t shy away from the gothic undertones; the darkening landscape behind her feels less like a backdrop and more like a character in its own right, a silent accomplice to the tragedy.

What’s fascinating, though, is how Waterhouse plays with the Pre-Raphaelite obsession with detail while still leaving room for the viewer’s imagination. The folds of Thisbe’s dress, for instance, are rendered with almost obsessive precision, but her face—well, her face is harder to read, half-turned away as if she’s already receding into the myth itself. It’s a neat trick, one that pulls you in closer while keeping the emotional core just out of reach. Compared to his more famous The Lady of Shalott, where the drama is all in the moment of crisis, Thisbe feels quieter, more resigned, as if the tragedy has already happened and we’re just catching up.

Waterhouse had a knack for picking moments that weren’t the obvious climax but still throbbed with tension. Here, it’s the second before Thisbe discovers Pyramus’s body, or maybe the second after—the painting refuses to pin it down exactly, which is part of its power. The landscape, dotted with those eerie, skeletal trees, doesn’t so much frame her as swallow her up, a reminder that nature in these myths is never just scenery. It’s always watching, always complicit. Funny how Waterhouse, for all his romanticism, never lets us forget that these stories usually end badly. Even the flowers at Thisbe’s feet look like they’re wilting in real time.

(c. 1380-1390)-full.webp)

-full.webp)

-full.webp)

-full.webp)

-full.webp)

-full.webp)