About the Artist

Master’s Palette

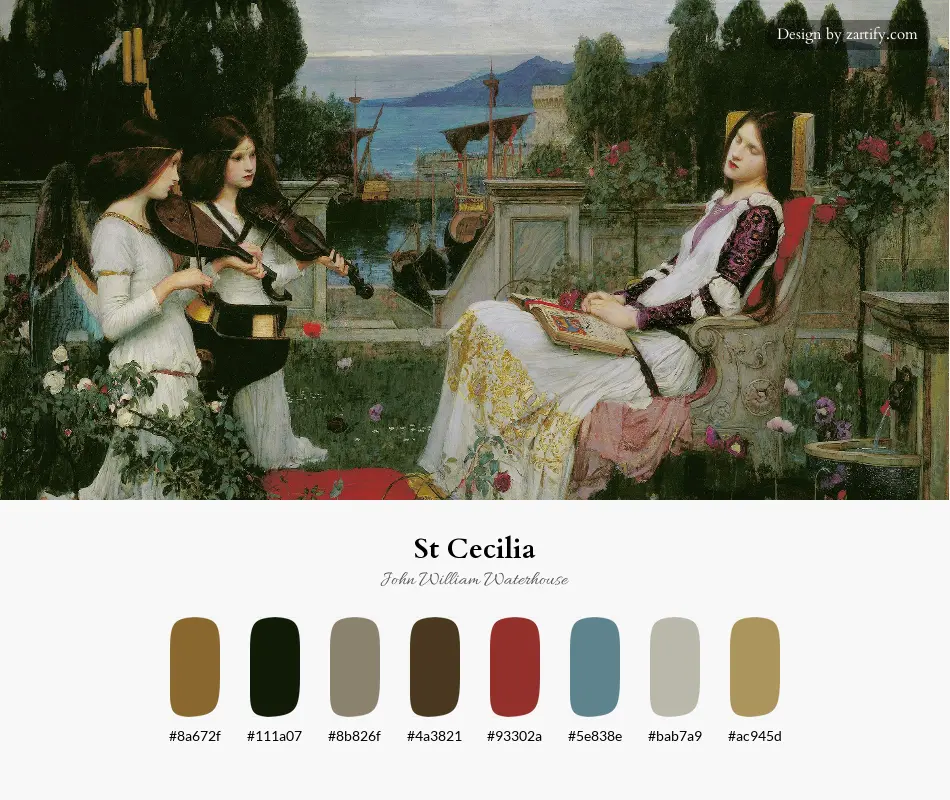

Reveal the unique color story behind each piece, helping you delve into the artistic essence, and spark boundless inspiration and imagination.

Bring the captivating colors to your project. Click to copy!

Artwork Story

John William Waterhouse’s St Cecilia is one of those paintings that sneaks up on you—it’s not as flashy as The Lady of Shalott, but there’s something quietly magnetic about it. The saint sits there, fingers resting on an organ’s keys, her gaze turned upward like she’s half in this world, half somewhere else. You know, that look people get when they’re listening to music only they can hear. The angel hovering beside her feels less like a divine spectacle and more like a quiet accomplice, which is interesting because most religious art of the period would’ve gone full Baroque drama with the subject. Waterhouse, though, he lets the moment linger. The palette is muted, all soft golds and deep blues, which somehow makes the whole thing feel more intimate than celestial. It’s less about the saint’s martyrdom and more about that private, almost mundane moment of connection with the divine—like catching someone mid-prayer when they think no one’s looking.

The Pre-Raphaelites loved their medieval revivalism, but Waterhouse always had a knack for threading the needle between myth and something almost uncomfortably human. St Cecilia isn’t as densely symbolic as, say, Rossetti’s work—no lilies or halos screaming their meanings at you. Instead, the symbolism is tucked into the details: the way her robe pools around her, the faintest suggestion of strings on the organ (though, let’s be honest, Waterhouse wasn’t exactly a stickler for historical accuracy when it came to musical instruments). Compared to his later, more theatrical pieces like Hylas and the Nymphs, this one feels almost introspective. You could imagine it in a dimly lit chapel, sure, but also in some collector’s study, the kind of room where the walls are too crowded with art and the air smells like old paper. There’s a warmth to it that doesn’t rely on grandeur—just a woman, an angel, and the quiet hum of something unseen.

Waterhouse’s saints always feel like they’re borrowed from poetry rather than liturgy, and St Cecilia is no exception. He wasn’t the first to paint her, obviously—Raphael did the whole heavenly choir thing centuries earlier—but his version strips away the pageantry. Even the angel’s wings are subdued, more feathery suggestion than gilded spectacle. It’s a reminder that Waterhouse, for all his Victorian trappings, had a way of making the mystical feel startlingly close. Funny how that works—sometimes the quietest paintings are the ones that stick with you longest.

(c. 1380-1390)-full.webp)

-full.webp)

-full.webp)

-full.webp)

-full.webp)

-full.webp)