-

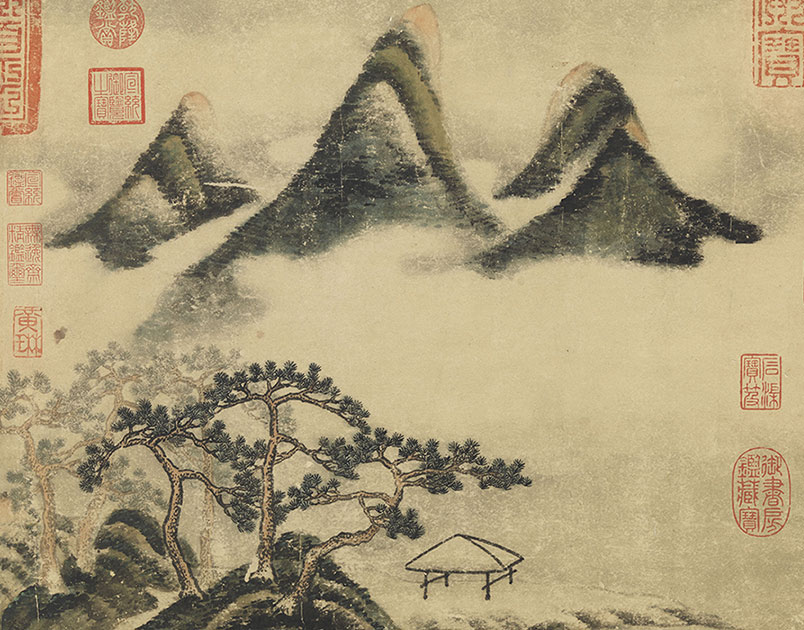

Snow Scenery Scroll. Song Dynasty. Ma Yuan

This work bridges Southern Song lyrical minimalism and Ming reinterpretations, offering insights into Ma Yuan’s enduring influence and the evolution of “academy-style” landscape painting.

-

Spring Festival Auspicious Scroll:Frozen Festivities in Ink

scholars in sable cluster around wine warmers while linen-clad servants stand frozen, unlit firecrackers dangling like Damocles’ sword. Hailed as “a pathological specimen of Ming genre painting.”

-

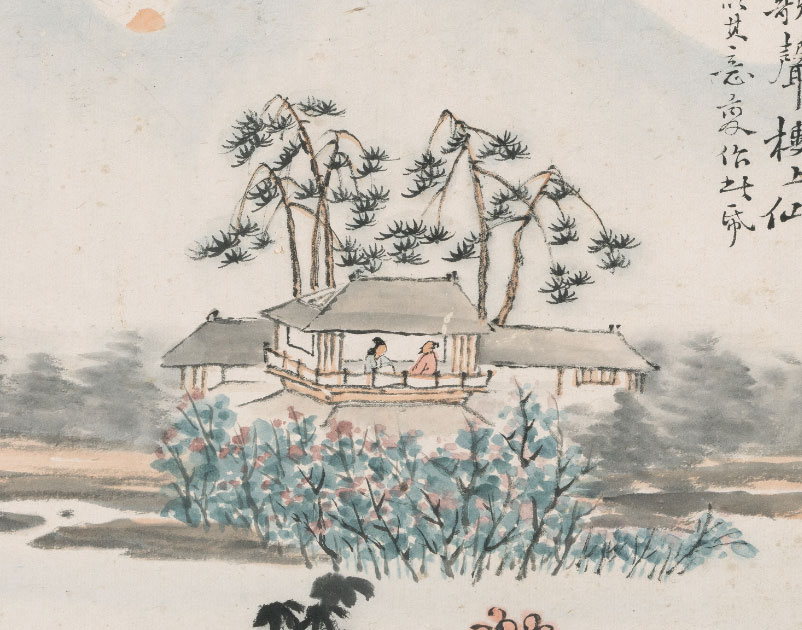

Spring Mountains and Auspicious Pines Scroll

Mi Fu’s “Cloudy Peaks and Pines” scroll whispers ancient burnout remedies through ink-wash poetry. The lone pavilion stands like a medieval mindfulness app icon, while mist-shrouded pines encode Song-era work-life balance wisdom.

-

A Silent Love Tragedy in Ming Art: Why Did Lü Ji Separate the Ducks?

Artwork captures emotional tension through minimalism: ducks turn away on a cold stone, duckweeds hover mid-fall. This Ming court masterpiece is hailed as “the spiritual breakthrough in bird-and-flower painting.”

-

Xia’ao Yanxia – Harmony with Nature and Inner Freedom

Artwork integrates landscapes and figures to express his profound contemplation of nature, reclusive living, and artistic philosophy.

-

Chang’e’s Flight to the Moon Handscroll, Tang Yin

This painting depicts the lunar goddess Chang’e holding a rabbit in quiet contemplation. Chang’e stands apart, her gaze introspective, as if pondering the bittersweet divide between immortality and human connection.

-

Scroll Painting of Chongyang Wind and Rain

Chrysanthemums bloom in abundance, while slanting wind and drizzle animate the scene.

-

Take you to see a different Along the River During the Qingming Festival.QiuYing

This world-famous masterpiece of social customs painting of the Northern Song Dynasty has spawned countless copies, imitations, different versions and re-creations. Among them, Ming Dynasty’s Qiu Ying’s “Along the River During the Qingming Festival” is the most famous.

-

Rediscovered Splendor: Imperial Artists Unveil Song-Ming Porcelain Masterpieces from Qianlong’s Secret Archives

Each album contains ten pieces of ancient porcelain (mostly works from the Song and Ming dynasties) selected by Emperor Qianlong. They were all drawn to facilitate Emperor Qianlong of the Qing Dynasty to appreciate the porcelain in the paintings.

-

Yongle Palace mural Chao Yuan Tu – an important masterpiece in the history of Chinese painting

As the art critic Wang Bonin noted, “This mural’s true value lies in its power to transcend time—a celestial parliament that speaks equally to the 14th-century pilgrim and the 21st-century viewer”.

-

Guiding Bodhisattva.Gold, Grace, and the Bodhisattva’s Promise in Tang Silk Splendor

Despite earthly glory, she follows the bodhisattva with humble reverence, her clasped hands and downward gaze embodying the Tang elite’s pursuit of spiritual liberation beyond mortal splendor.

-

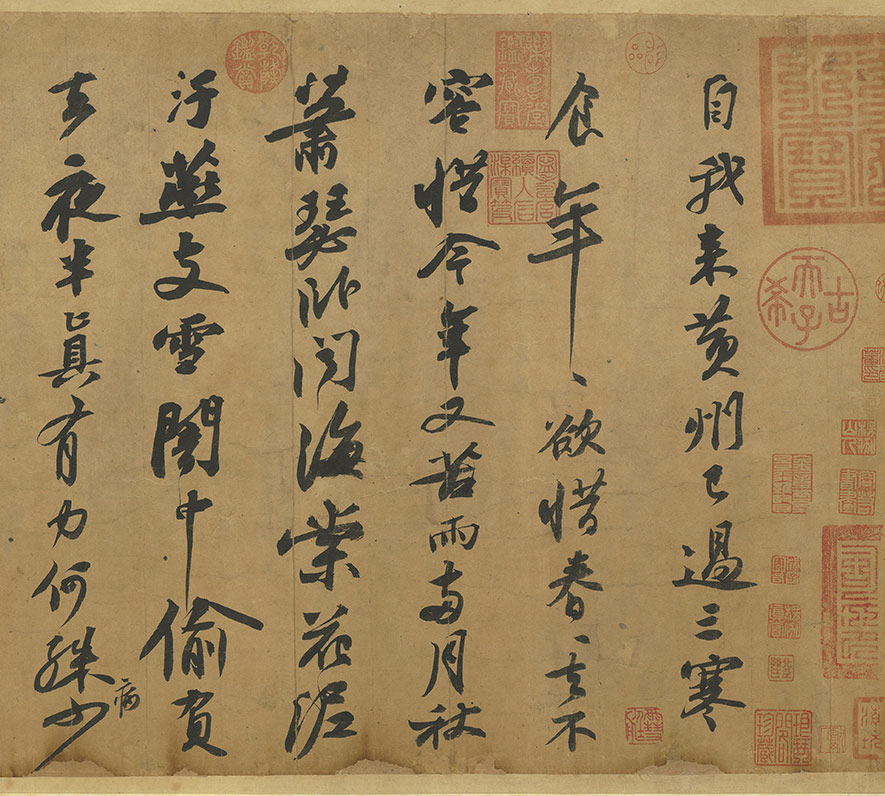

The Cold Food Observance, from Ashes to Immortality: How a Banquet of Words Defied Time

The scroll’s spatial composition (bubai 布白) transcends mere aesthetics, becoming a cartography of the poet’s psyche—where ink and void converse like lamentations and silences.

-

Time-Travel Through Petals: The 2,000-Year-Old Art of Reading Nature’s Clock in Chinese Paintings

“Flower-Signal Wind” refers to the seasonal breeze that brings the message of blooming flowers. According to the traditional Chinese calendar, the period from Lesser Cold to Grain Rain comprises eight solar terms over four months. For each segment, a flower that most accurately embodies its blooming season is chosen to symbolize the “Flower-Signal Wind.

-

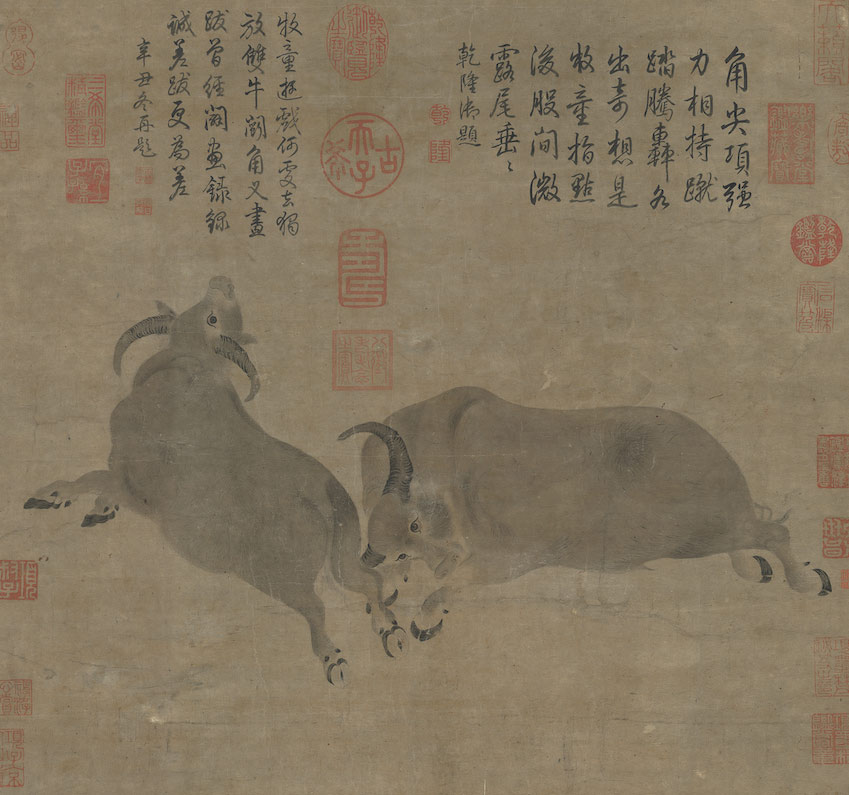

Roaring Strength on Paper: Experience the Intensity of Dai Song’s Tang Dynasty Bullfight

The bulls are portrayed with robust, muscular forms and a palpable vitality, evoking an impression of raw power that seems capable of overwhelming multitudes.

-

How did the top painter of the Southern Song Dynasty become famous

The painting captures a serene spring scene: willow-draped cliffs, a scholar’s boat drifting on tranquil waters, and a distant dock veiled in mist.